The Aesthetics of Geopower: Kinetic Art, the Guri Dam, and Environment-Making in Venezuela

In the 1970s, as Venezuela rode the wave of one of the greatest oil booms in its history, abstract kinetic art (also called “cinetismo”) rose to the status of official visual language of the nation’s modernization projects. Reaping the benefits of the oil price hikes caused by the OPEC embargo of 1973 (a product of the October Arab-Israeli war), the social-democratic government of Carlos Andrés Pérez (1974-79) launched a large-scale developmentalist program known as the “Great Venezuela.” As a period of rapid urban expansion unfolded, the country became replete with eye-catching, ultra-modern murals and sculptures by Alejandro Otero, Jesús Soto, and Carlos Cruz-Diez, the holy trinity of Venezuelan cinéticos. Government initiatives such as the Museo Ambiental, launched in 1975, intensified the relation between abstract kinetic art and the era’s ambitious environment-making efforts, which led to a radical transformation of the national landscape in only a few years. In a moment that may well be regarded as the peak of this imbrication between kinetic art and oil-led modernization, Cruz-Diez and Otero were commissioned to produce two oversized works to be integrated into the Guri dam (the world’s largest hydroelectric power plant at the time), built on the Caroní River in the resource-rich region of Guayana (Figure 1).1 At its final inauguration in 1986, the dam’s massive turbine halls boasted a pair of Ambientaciones cromáticas [Chromatic Environments] made by Cruz-Diez, with a total surface area of almost three acres. As the turbines extracted electric power from the waters of the Caroní, Cruz-Diez’s colorful, vibrating murals performed a conversion of their own—that of the raw materials of metal and industrial paints into ethereal hues that appeared to come to life. Outside the dam stood Otero’s Torre Solar[Solar Tower],a 150-feet tall machine-like steel sculpture that rotated with the wind, creating a spectacle that seemed to harmonize technology and nature. In the institutional publication El arte en Guri, prominent art critic Alfredo Boulton characterized the works by Cruz-Diez and Otero as an homage to the “new Venezuela” ushered in by the Guri dam, “donde apenas hace un siglo nada había, sino leyendas, bosques, ríos y mitos” [where only a century ago there was nothing except legends, forests, rivers, and myths].2 Similar ideas about cinetismo were amply disseminated through state-financed publications like Imagen and Revista Nacional de Cultura,government-friendly popular magazines like Momento and Élite, newspapers, books,3 and even TV specials and films4 that highlighted the alliances between cinetismo and the nation’s accelerated modernization process.5 In this way, if kinetic art was shaped by the state’s environment-making and urbanization projects, it also attained the status of agent of ecological transformation by helping to remake the physiognomy of modern Venezuela.

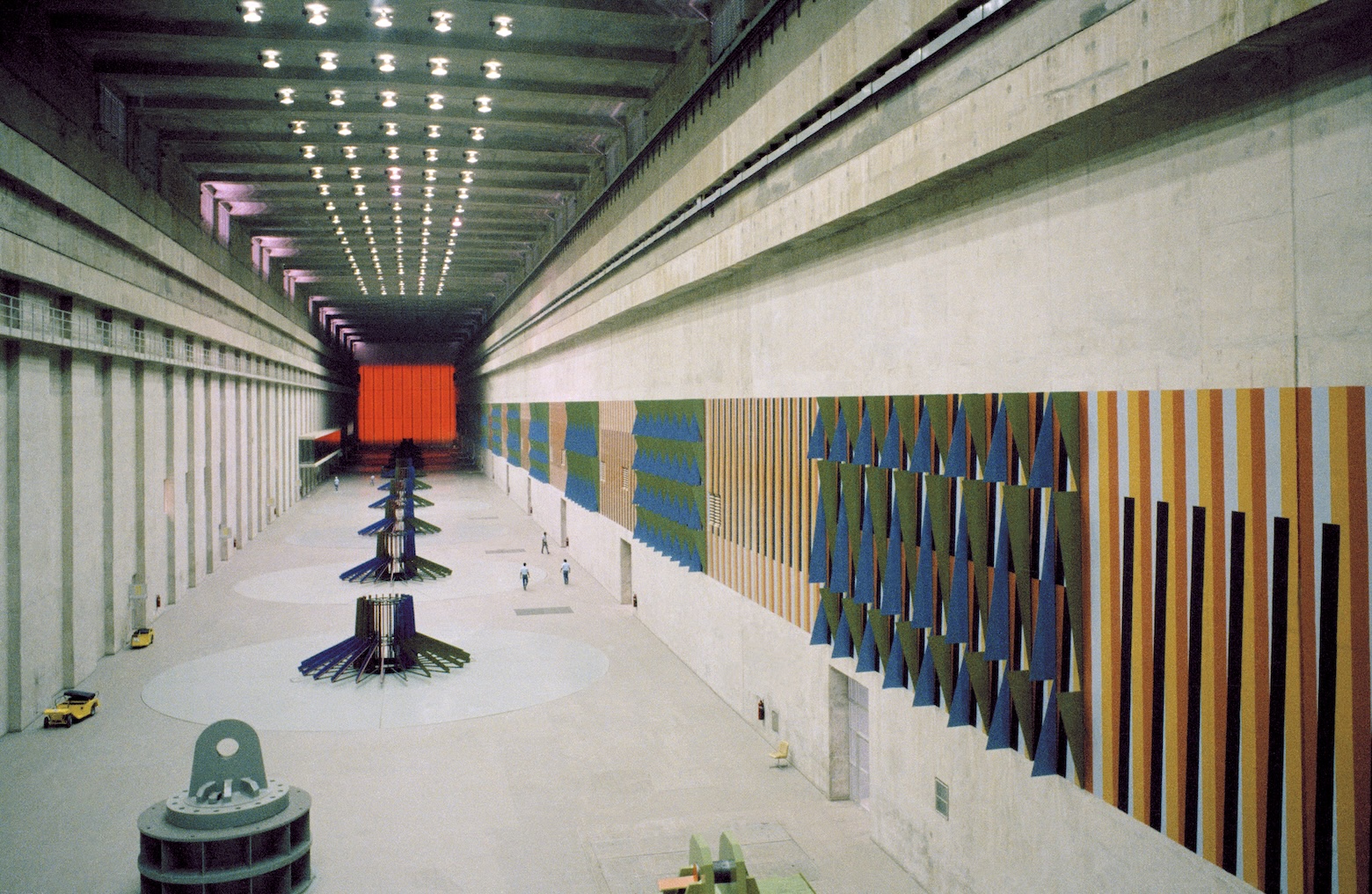

Figure 1:Simón Bolívar Hydroelectric Power Plant (Guri dam). Courtesy of Corporación Eléctrica Nacional, C. A. (Corpoelec), 2009.

However, cinetismo’s takeover of the national landscape did not unfold without its fair share of criticism. Already in 1974, Argentine critic Marta Traba saw the hegemony of kinetic art as a reflection of Venezuela’s compulsion to give itself a “façade” of progress to mask deeper social issues like socioeconomic underdevelopment and the lack of an original cultural identity.7 The critic also scorned the creation of the Jesús Soto Museum of Modern Art in 1973, built on the hot and humid banks of the Orinoco River near the Guri Dam, and largely dedicated to the promotion of cinetismo. 7 Kinetic art, Traba argued, offered an inadequate response to Venezuela’s identity and social dilemmas, and portrayed it merely as an “official art” catering to the questionable tastes of the petrodollar-flush ruling elites.8 Traba’s insights continue to resonate in contemporary studies of Venezuelan abstract and kinetic art, where the works of Cruz-Diez and Otero are frequently seen as ideological artifices that symbolically erased or resolved the shortcomings of oil-centered modernization (namely rising inequality, economic backwardness, foreign cultural dominance, and local environmental degradation). 9 While it is undeniable that cinetismo was complicit with petroleum-driven development, more can be said about the specific relations between abstract kinetic art and the broader national ecological shifts of the 1970s, including extensive urbanization, the expansion of the extractive industry, and the construction of large energy infrastructures. Was cinetismo, as Traba claimed, simply out of touch with its national context? Was it propaganda, a flashy distraction from socioeconomic backwardness? Or, upon closer examination, did it contain an aesthetic theory that actively supported the larger ambition of harnessing the nation’s social and natural energies?

In this article, I present an alternative reading of cinetismo as a constitutive part of the mobilization of ecological forces required by the environmental project of the Great Venezuela. I analyze the artworks made by Cruz-Diez and Otero for the Guri hydroelectric dam to argue that, rather than an ideological cover upon the failures of the oil state, cinetismo played an internal role in the history of ecological transformations in Venezuela in two interrelated ways. First, by contributing to the collective understanding of nature (and not only petroleum) as a stock of resources to be harnessed and put to work in the service of national development. Secondly, through its direct involvement in a history of large-scale environment-making projects supported by nature extraction. In consequence, as I contend, cinetismo was a fundamental cultural device of geopower, a concept that describes the mix of science, culture, and power that enables the remaking of the earth.10 My guiding assumption is that Venezuelan kinetic art can be understood as part of what Jason W. Moore calls capitalism’s “repertoire of strategies for appropriating the unpaid work/energy of humans and the rest of nature.”11 In this way, the case of cinetismo provides insights into how geopower relies not only on practices of techno-scientific visualization, but equally on strategies of cultural production necessary to turn local ecologies into appropriable natural resources.

My article builds on the work of scholars in the environmental humanities who have studied the place of literature and the arts in the entwined histories of capitalism and nature. In particular, I am in dialogue with recent efforts aimed at picking apart the cultural narratives that sustain the power of extractive regimes in the Global South. I approach my objects from the perspective of world-ecology, an interdisciplinary field spearheaded by Moore, which conceives capitalism as a socioecological web premised on putting all of nature to “work” in the service of capital with the crucial intervention of culture and the state. Following Moore, recent scholarship suggests that the role of culture in the world-ecology extends beyond an immaterial superstructure and is not confined to the reproduction of class ideologies or the mere reflection of the social world. Daniel Hartley conceives culture in the broadest sense as one of the basic processes through which economic and social structures are formed, arguing that it should be studied as a “materially constitutive and productive moment in capitalist value relations.”12 Sharae Deckard has studied a wide array of examples from Latin American fiction, concluding that literary production can function as a productive force in the world-ecology by “imagining, producing, and stabilizing new social relations, epistemes, and technics,” which can serve to either legitimize or resist nature extraction in the periphery for the benefit of core nations.13 Lastly, Chris Campbell and Michael Niblett understand literary practice as an aesthetic modality of environment-making, as it can contribute to the reconfiguration “of patterns of land use, of labouring practices, of attitudes to ‘nature,’ and so forth,” which help to reconfigure the place of human and extra-human natures in the world-ecology. 14 Nonetheless, the role of visual cultures and the arts as historical agents in world-ecological processes is one question that the field has still not fully addressed. In this way, the active and constitutive role played by forms of cultural imagining such as photography, film, or even abstract art is still to be articulated, even though they have long been implicated in processes of modernization, environment-making, and geographical governmentality in Latin America. The same can be said for the analysis of public cultural institutions and the cultural work of states, especially during periods of intense ecological transformations. The field of world-ecology is thus ripe for the kind of questions that this article brings forth.

Geopower, Visual Culture, and the Ecology of Capitalism

The concept of geopower has developed in recent years across several fields encompassing political theory, environmental history, anthropology, and philosophy. Simply stated, it refers to the knowledges, powers, and symbolic practices that make it possible to transform the earth in order to place it in the service of capital.15 The term initially emerged in dialogue with Foucault’s notion of biopower, largely as an extension of its scope in order to account for the relations of co-production between human and extra-human natures. If biopower names the scientific knowledges and technologies that make biological life the object of politics, then geopower addresses the continuum spanning both the living and the non-living, the mineral and the biological, and the organic and inorganic elements that make up the earth (e.g., the atmosphere, water, energy, and so on). Central to my analysis is the conception developed by Moore, who argues that capitalism depends on strategies for appropriating nature that “cannot be reduced to so-called economic relations but are enabled by a mix of science, power, and culture.”16 Geopower names this mix of forces that enables capitalists and state machines to symbolically render appropriated natures into the abstract and interchangeable units (e.g., “resources” or “natural capital”) fundamental to the production of value. In other words, geopower acts through the production of what Moore calls “abstract social nature,” which in turn serves to fashion nature into a motor of capital accumulation.17

To illustrate the ideological and cultural aspects of geopower, Moore uses the example of hydroelectric dams. He explains that dams are one of the technologies that put nature “to work” as part of the “radically expansive, and relentlessly innovative quest to turn the work/energy of the biosphere into capital.”18 However, dams are also fundamentally dependent on “a collective understanding that cheap energy is part of the nationalbounty.”19 Therefore, in the same way that a megadam requires the work of technicians and engineers, it also demands that certain ideas about nature be disseminated through the social body with the crucial help of specific discourses and strategies of cultural planning.

For their part, Bonneuil and Fressoz observe that, since the Cold War era, geopower has been increasingly assisted by photographs of the Earth seen from space, like the so-called “blue marble” or “Spaceship Earth” that became popular in the environmentalist discourses of the 1970s.20 These images, which defined the character of the era’s conservationist policies, were functional to what Timothy Luke calls the “eco-panopticon” of contemporary geo-managerialism, which re-envisions nature as a fragile system of resources to be piloted by humans.21 It was also during this time that the idea of “the environment,” a rather vague signifier, lay the ground for new ways of inhabiting the earth in which “geopower exhorts its subject … to ‘reconnect with the biosphere.’”22 Geopower and what Moore and Patel call “the cheap nature strategy”23 are at work precisely in such articulations between capital, state power, nature, and the work of culture. As Moore states, “abstract social nature” is not “just there,” but is “actively constituted through symbolic praxis and material transformation.”24

The role of visual culture and visualization technologies in the historical development of geopower cannot be overstated. As Moore and others have pointed out, geopower has typically been exercised through practices of visualization like mapping, surveying, and satellite photography, all of which are fundamental tools of geogovernance. Nonetheless, the visual dimension of geopower has thus far been analyzed in relation to techno-scientific practices that aim to produce exact representations of geographical features. This has left the aesthetic and cultural aspects of geopower largely undertheorized, and the relationship between geopower and the arts in general—not to mention examples of non-representational art like kinetic art—barely elucidated.25 My wager is that undertaking this task requires that we look at culture both as a space of aesthetic forms and as a material web of products and producers, institutions, discourses, money flows, and ecologies where collective agreements about nature are forged and maintained. I choose the example of Venezuelan cinetismo precisely because, more than simply a style, it was a wide visual culture phenomenon encompassing publications, films, and cultural institutions, as well as state and private agencies in charge of urbanization projects and geographical governmentality.

I am not the first to propose a spatio-cultural reading of Latin American abstraction. Luis Pérez Oramas has argued that abstract constructivism, including cinetismo, can be understood not as a style but as a site or, more exactly, as “a system of topoi or ‘topologies’” that constructed the illusion of “modernity as a place.”26 Juan Ledezma has also thought Latin American abstract art as a collection of sites but he bundles these places with the cultural products (such as photographs and books) that disseminated sensibilities and ideas related to a strictly industrial notion of modernity.27 Alexander Alberro uses the notion of “aesthetic field” to argue that in Latin American abstraction meaning was constructed relationally across a space that encompassed art objects, their places of display, and their spectators, as well as the critical discourses around those works and the aesthetic theories espoused by the artists.28 While mine is not an art-historical approach, I am informed by these and other scholars who discuss how the production of space has long been a part of the political function assigned to art in the context of Latin American modernization. Discerning how geopower can be supported by the work of the “aesthetic field” would allow us to expand its definition to include not only visual representations of the earth, but also creative and artistic commitments that equally support projects of geographical governmentality.

Hydroelectric Dams and the Remaking of a Nation

The 1970s oil boom created the illusion, to quote Venezuelan anthropologist Fernando Coronil, that “the flow of history could be redirected, that oil money could launch the country into the future and grant it control over its own destiny.”29 Coronil’s words capture the essence of the era’s collective wish—to take control of a chaotic, shapeless “flow” and channel it into the image of a modern nation. Likewise, the dream of the Great Venezuela of the 1970s could only be achieved after seizing the potential of the country’s natural wealth (not only oil, but also iron, gold, bauxite, and hydropower). Because of its large reserves of minerals and the energy potential of the Caroní River, the vast highland of Guayana (which comprises slightly over half of Venezuela’s territory) was seen as the keystone of the country’s development plans. The “electrification of the Caroní,” a persistent national aspiration since the 1940s, sought to harness the enormous potential of the river and translate it into the cheap electricity upon which the nation’s modernization plans depended.30 For this purpose, the company Electrificación del Caroní, C. A. (Edelca) was created in 1963 to kickstart the construction of Guri under the supervision of the state-owned conglomerate Corporación Venezolana de Guayana (CVG). At 10,300 MW of installed capacity, the dam would provide over 70% of Venezuela’s electricity and save the country around 300,000 barrels of oil per year that could be sold in the international market instead of burned for electric power at home.

As key protagonists in narratives of national progress, large dams are also materializations of political, economic, and social power. As Max Haiven argues, “dams are fundamentally cultural edifices: not only do they organize waters but they organize meanings and relationships.”31 At the same time, they function as sites where national meanings and energies pool together, like “turbines of subdued and churning meaning-making.”32 In the case of Venezuela, Guri was one of those key sites in the remaking of both nature and nation. A compulsory stop in the regional touristic itinerary until the early 2010s (and open to visitors of all social ranks), its purpose went well beyond the practical and was both a technological and artistic landmark that seemingly reconciled engineering and cultural distinction.

Developed in the context of the Alliance for Progress of the 1960s, the dam also fulfilled a political role that solidified Venezuela’s position in the orbit of the United States and kept it on the path of Western-style development. In turn, it was presumed, that integrating Venezuela further into the capitalist world market would help to secure the region against the spread of communism. This is why, in his inauguration speech at the completion of Guri’s first stage in 1968, President Leoni made sure to underline his role in achieving “institutional and democratic normality” against the threat of “external forces” and “internal subversion,” in an implicit reference to Cuban influence on Venezuelan and Latin American leftist armed movements.33 At the finalization of the dam’s second stage in 1986, and almost twenty years after leftist guerrillas had been “pacified” in Venezuela, these meanings were still associated with the dam. This same year, Edelca commissioned the glossy full-color hardbound book El arte en Guri, written by Alfredo Boulton, to promote the dam and the colossal artworks by Cruz-Diez and Otero. In its pages, the critic drew a parallel between the triumph over the turbulent waters of the Caroní River and the birth of a new nation, and between the production of new geographies and the production of a new society:

All that world of vegetation, of primary force, of mysterious jungles, boas and of cataclysmic echoes; all that magic spell suddenly comes to a halt on the gentle shore, turned lake, before the great Dam ... So it happened on the first day of the universe, it is also the creation of a new country, a new Venezuela.34

The book’s photographic sequence speaks for itself. In the first twenty-nine pages, the text is accompanied only by images of the intricate jungles of Canaima and the rapids of the Caroní. Then, abruptly, a double-page photo shows the placid human-made lake. The reader has been carried away from the maelstroms and steep waterfalls of the Caroní onto the impoundment that results from the containment of the mighty currents. The river, being funneled into the turbines of the power plant, has seen its furious and raw energy effectively pacified and transformed—as if by a flip of the page—into useful hydroelectric energy. The enormous reservoir, with its flat and almost polished surface, should also be understood as a docile and governable space. In this visual narrative, the reservoir itself becomes a metaphor not only of tamed nature but also of a social body that until very recently had been shaken by the turmoil of leftist armed insurgency. In this way, the idea of achieving dominion over the Caroní’s free-flowing energy and the goal of controlling undomesticated social forces were dual aspects of the modernization project that was embodied by the dam. Guri can thus be seen both as the materialization of national aspirations (within an international capitalist frame) and of a specific form of authority that has the power to remake the nation—global geopolitics supported by local geopower. In the remainder of this article, I analyze the works and discourses around the works created by Cruz-Diez and Otero for Guri, placing them in the larger context that made cinetismo the paradigmatic visual language of the state’s plans to translate Guayana’s ecology into an ordered, manageable network of resources integrated to the world economy.

Figure 2:Carlos Cruz-Diez,Ambientación Cromática (Fisicromía y Cromosaturación murales con Cromoestructuras cónicas), ١٩٧٧-١٩٨٦.Engine room No.2, Simón Bolívar Hydroelectric Plant, Guri, Venezuela. HT. 28 x W. 26 x D. 300 m [92 x 85 x 984 ft.]. Eng. Herman Roo, Argenis Gamboa, Efraín Carrera, Gerardo Chavarri. Photo: Atelier Cruz-Diez Paris. © Carlos Cruz-Diez / Bridgeman Images 2021.

Figure 3: Carlos Cruz-Diez,Ambientación Cromática (Murales de Color Aditivo con Cromoestructuras circulares), 1977-1986. Engine room No.1, Simón Bolívar Hydroelectric Plant, Guri, Venezuela. HT. 26,5 x W. 22,5 x D. 263 m [87 x 74 x 863 ft.]. Eng. Herman Roo, Argenis Gamboa, Efraín Carrera, Gerardo Chavarri. Photo: Atelier Cruz-Diez Paris. © Carlos Cruz-Diez / Bridgeman Images 2021.

Cruz-Diez: Capturing Color

Cruz-Diez’s Ambientaciones cromáticas took nine years to complete from the moment of their commission by Guri’s engineers in 1977. Turbine hall number 1 encloses 78,500 square feet of multicolored stripes directly painted on the concrete walls (Figure 2). On top of the generators are ten metal and fiberglass “chromostructures” in the shape of truncated cones (each 6.5 feet tall and 46 feet in diameter), whose vibrating colors over the sleek black floor suggest the rotating motion of the engines below. Turbine hall number 2, much larger than the first, has one 580-feet-long chromatic mural (Figure 3). Their patterns were designed to align perfectly with the grooves left on the concrete by the formwork during construction, with the intention of making them optically disappear. A group of painted metal structures protrude from its surface to create the effect of a field of color that evolves depending on the viewer’s position in space. At the back of the room is a “chromosaturation” panel consisting of a wall of 1,200 red, green, and blue light bulbs with a varying color sequence that can be controlled by the visitors from a mezzanine deck at the push of a button. Over the turbine shafts, a similar set of 10 chromostructures, only much taller—13 feet tall, 26 wide. The result is an immersive environment where color becomes a lived situation that directly involves and implicates the observers. As color is transported into space, visitors are also made part of the works, as their movements, bodily dispositions, and capacities to perceive become the ingredients that set the chromatic experience in motion. In their eyes, the murals become inseparable from the engine room, making the dam a hybrid between art and infrastructure that seems as much a work of Cruz-Diez as it is of the engineers that designed and built it.

The color-bathed atmospheres inside Guri’s turbine halls were an appropriate culmination for Cruz-Diez’s experimentations with color since the early 1950s. His quest, thoroughly explained in his book Reflexión sobre el color from 1989 (published only three years after the completion of his works at Guri), can be summarized as follows: To liberate color from its material ties—to “dematerialize” it—in order to present it as what it really is, an ephemeral and affective phenomenon removed from both matter and form. He added that the “apprehension” of color by the viewer was a phenomenological process mediated both by cultural determinations (references, preconceptions, myths) and the bodily senses of the observer, where the affective qualities of colors were ultimately decided.35 Therefore, it was the work of the artist to seize those chromatic, “natural” events, detach them from their symbolic and material ties, and present them under a new light as the unstable, unbound, and unsubordinated realities that they truly were.

Cruz-Diez’s defining breakthrough came in 1959 when he noticed that, around the area of contact between two thin strips of cardboard (one green and one red) over a black background, a third color (yellow) appeared as a floating optical illusion. This yellow, which he called Amarillo aditivo (Additive Yellow), was not chemically present on the surface but rather resulted from the sum of the afterimages of red and green blending in the retina (hence, its additive quality). Pure and isolated color, stripped of its material, formal, and symbolic ties. This was the basic device that allowed Cruz-Diez, in the words of critic Ariel Jiménez, to “capture a fleeting moment in nature [i.e., color]” and “to present [it]—free and unattached—in space and time.”36 The serial accumulation of similar modules of additive colors constituted what the artist called a physichromy, such as the ones that cover the walls inside the Guri Dam.

Cuz-Diez’s architectural and urban integrations evolved from the desire to transpose the immaterial colors of his first physichromies into spaces that could be penetrated by the viewer. His designs since 1965 for chromosaturation chambers, where visitors would be bathed in red, blue, and green light emanating from ceiling neon lamps as they moved through labyrinthine corridors, were a first step towards this goal. In 1969 he built and installed in the streets of Paris a series of ephemeral booths made of colored transparent PVC panels and neon light fixtures from which visitors could witness a city transformed by color. Breaking down the natural phenomenon of color into its basic components allowed Cruz-Diez to create immersive, simplified atmospheres that he hoped would “recondition” and awaken spectators to a primary experience of reality that would free them from their “cultural conditioning.”37

Cruz-Diez later transposed these principles to his permanent interventions in urban space, including the floors and walls of the main hall of Maiquetía International Airport, the crosswalks in Sabana Grande district, the underground chamber at José Antonio Páez power station, and other examples made for private and public buildings throughout the 60s and 70s. If this expansion into a broader aesthetic field was meant to have an effect on subjective experience, it also acted as a force of environmental transformation, both in the production of ideal spaces for experiencing pure color and in the ways that his works shaped the physiognomy of Venezuelan urbanization. By incorporating his works into urban and industrial environments, the project of reprogramming the social body through action on the senses could be expanded into wider mechanisms of public participation cemented on the sensation of pure color. However, for this utopian articulation of object and subject to succeed—wherein the spectator was recast as a participant in the artwork—colors first needed to be isolated and reduced to manageable units stripped from their entanglements with nature’s history.

Such ideas were explicitly articulated by Boulton in El arte en Guri, mentioned above, where the critic wrote at length about Cruz-Diez’s works. There, Boulton described colors as “active dynamos” and claimed that the task of the artist consisted in the “capture” of the electromagnetic flows “that all objects enclose,” in the same way that the dam captured and transformed the free-flowing energy of the Caroní River.38 In an earlier newspaper article, Boulton contended that Cruz-Diez’s treatment of color was an “alchemic” process through which color was first extracted and then placed under the command of the artist and his work.39 These identifications between the artist’s work and the mastery of nature were widely disseminated through public artworks integrated into urban spaces, as well as generous investment publications and films with the direct financing of state corporations like Edelca. In this way, the political work performed by the state-culture nexus sought to build a collective understanding of free-flowing nature (be it hydropower, buried minerals, or natural phenomena such as light and color) as resources ready to be harnessed and put to work in the service of a “new” nation.

Nevertheless, there remains an unresolved tension in Cruz-Diez’s work between capture and release, freedom and containment. Visitors of chromosaturation chambers are compelled to free themselves from the strictures of cultural conditioning, but first, they must be “forced” to linger in the color-saturated labyrinths.40 Color is freed from its formal and material prison, but only to be subordinated again to the artist’s ability to make environments and atmospheres (such as the environments in the turbine halls at Guri) where it can be experienced as an aesthetic event. In the same manner, color is seen as autonomous, but this autonomy is ultimately subjected to strictly human bodily senses and capacities of perception. Ultimately, the works of Cruz-Diez were devices that simplified nature (e.g., light and color) into isolated units that could be presented as aesthetic events, but always within controlled environments of the artist’s design. The primacy of human sensation in his work conditioned beforehand the existence of color only as extracted resource to be mobilized, imbued with a life of its own that nevertheless was under the command of the artist (even when spectators completed the work through their active participation). In this sense, the visual spectacle of the turbine halls at Guri could not have been accomplished without a preceding radical simplification of nature through which the ideal purity of color was seized and redirected to serve human ends.

Figure 4:Alejandro Otero,Torre Solar, 1986. Stainless steel and concrete, 160 x 170 ft. Simón Bolívar Hydroelectric Plant, Guri, Venezuela. Photo: Domingo Álvarez. Courtesy of Alejandro Otero-Mercedes Pardo Foundation.

Otero: Technologies of Redemption

As Cruz-Diez’s colors engulfed the atmosphere inside Guri’s turbine halls, Otero’s Torre Solar, the artist’s largest and most ambitious work, stood outside near the dam’s spillway (Figure 4). Completed in 1986 by Hitachi (the same Japanese company that provided the dam’s turbines and installed its computer systems), it rose 160 feet tall and had a hollow concrete core clad in 57 tons of burnished stainless steel. At its top, two concentric circles, spanning 170 feet wide, rotated in opposite directions as the wind flowed through them. Like Cruz-Diez’s vibrating chromostructures, the tower’s movements echoed the rotation of the turbines inside the dam, producing a mesmerizing display of reflections as the metal fins caught the shifting colors of sunlight throughout the day. The sculpture evolved with the action of atmospheric forces, remaining still on calm days until the wind sent it spinning with an audible roar.

The sculpture’s polished, gleaming silhouette contrasted with a cluster of five hundred Precambrian boulders blown with dynamite from the Caroní riverbed and placed around its base. The machine-like structure emerging from the roughness of the boulders seemed to express confidence in the nation’s future, which in this case appeared to spring directly from the soil. This is why Otero compared his sculpture to “a technological flower sprouting from the earth.”41 In this metaphor, technological development springs from the soil, conjuring up the dream of realizing the future by metabolizing natural wealth into the image of a sophisticated and modern nation. In this sense, the sculpture replicated the broader role that the state played in Venezuela, which—according to Coronil—functioned as the agent capable of magically metabolizing raw subterranean matter into the visible signs of modernity.42

More importantly, in the words of Otero, the aesthetic effect produced by the tower’s flickering motion had a redemptive quality that sought to symbolically repair the ecological impact of the dam: “Its metallic reflections, its movements combined with the sun and the wind, tend to restore the grace, the transparency, the luminosity of the river, now underground.”43 If Otero could, in fact, recreate the aesthetic qualities of the Caroní, then his sculpture could stitch back together what the dam had cut apart, becoming in this way a sort of redemptive machine within the cultural workings of geopower. Offering a glimpse into an already achieved modernity that sprang out of raw subterranean nature, the Torre Solar not only set in motion the forces of metal, sunlight, and the wind but also the dreams and anxieties of a country impatiently trying to realize its future.

Otero’s interest in industrial aesthetics can be traced back to 1954, when he made an aluminum and concrete monolith for a Shell gasoline station. However, it was not until the late 1960s that he would fully adopt machine-like sculptures as his preferred means of artistic practice. His embrace of steel and aluminum kinetic artworks for urban spaces since 1967 (which he grouped under the broad category of “Spatial and Civic Structures”) was a transition that he understood in various related ways. First, as a move beyond the enclosed and privileged domains of museums and private collections, where his acclaimed Coloritmos of the 1950s had thrived as emblems of bourgeois distinction.44 Reconceived as self-supporting urban structures of a different scale (larger works for larger crowds), his artworks would no longer be subordinated to private spaces or gas stations; instead, they would be able to reinvent the city by themselves. Secondly, but no less important, Otero’s spatial and urban sculptures were the result of a deepening of his confidence in the transformative powers of scientific and technological advancement.

There is no doubt that Otero’s works were closely associated with Venezuela’s extractive industry, for example, through the state corporations that financed them, the origins of their materials in the extraction of resources (like iron, and bauxite for making aluminum), and their physical emplacement at places like Guri and the Orinoco Steel Mill offices in Ciudad Guayana (as in the case of Otero’s Integral Vibrante of 1968). Nevertheless, as governments of the period adopted an incipient ecological discourse and introduced new conservationist policies (such as creating the first national parks and environmental management agencies), cinetismo was reframed as disconnected from the industry’s negative impacts on the environment. Even as Otero’s works helped to shape meanings that were functional to geopower’s capacity to remake the earth, the critics consistently praised them for being “idle technological constructs” or “useless machines.”45 Some went so far as to categorize Otero’s sculptures as “environmentalist works” that became harmlessly integrated into the climatological elements, on account of their reliance on sunlight and wind.46 The assumption was that Otero had achieved an art comparable to the advancements of modern technology, but without it becoming subordinated to the realm of industrial function. The real links between Otero’s sculptures and the industrial world were thus downplayed by metaphors that glorified how Otero’s sculptures brought art and technology together (at the level of technics), but set them apart (at the level of industrial function).

Paradoxically, to achieve their aesthetic productivity (after their detachment from functionality), Otero’s sculptures had to optically dematerialize through a fast spinning motion, an effect exacerbated by the ethereal reflections produced under sunlight and light reflectors. Not by coincidence, night photographs of the Torre Solar used long exposure to create blurry, swirling images that emphasized how the cold steel blades nevertheless concealed a fluid, evanescent character that prevailed when they realized their kinetic purpose. The collective consensus around these ideas, propagated through a wide array of private and state-financed cultural products related to the Guri Dam—such as Bouton’s El arte en Guri and Otero’s Saludo al siglo XXI—situated Otero’s work in an ideal position to symbolically replot the hydroelectric dam’s impact on the river’s ecology as “the highest monument to the glory of the Caroní.”47

As Leo Bersani argues, these kinds of assumptions about art’s redemptive qualities are part of modernism’s “culture of redemption,” which posits that art has the task of repairing the catastrophes of history: “[in modern high culture] it is assumed … that the work of art has the authority to master the presumed raw material of [traumatic] experience in a manner that uniquely gives value to, perhaps even redeems, that material.”48 Bersani shows that such symbolic acts of reparation take the form of a repetition or reenactment that deprives historical facts of their experiential “truth” through artistic representation. However, and as he concludes, this approach to art produces a “devaluation” of both art and historical experience, because the catastrophes of history seem to matter less than their symbolic transcendence, while art is reduced to “a kind of superior patching function” that ends up enslaving it to the very materials which it presumably repairs.49

The Guri Dam’s Torre Solar is the prime example of Otero’s attempts to redeem the geo-managerial project of the Great Venezuela of its real impacts on nature. This is why, as I noted at the beginning of this section, Otero compared it to a “technological flower” capable of restoring the isolated aesthetic qualities of the Caroní—its “transparency,” “luminosity,” and “grace”—right at the point where the river had been sliced by the hydroelectric dam.50 The Plaza de la Democracia on which it stood, made by rearranging the boulders previously blown up from the Caroní riverbed, complemented the idea that artistic intervention in nature was an act of putting back together what industry had torn apart. But as the work became subordinated to this restorative function, the traumatic event of the dam’s appropriation of the work/energy of nature, reenacted by the Torre Solar’s turbine-like motion, was dissolved by the aesthetic machinery of representation and thus deprived of historical substance. In Otero’s utopian belief in the harmony between technology and nature was embedded a contradictory project that attempted to restore nature by incorporating it as the simplified elements (e.g., the wind, the sunlight) that fueled the aesthetic event of his works. His invitation to reconnect with nature—understood not as an unsubordinated mixture of human and extra-human ecologies but, rather, as an environment under human command—was in itself a strategy of geopower.51 The very operation of optical self-dissolution that characterized his inventions, expressed in the way that his sculptures became integrated with the “elements,” was not possible without a previous capture and reorganization of nature in the service of human perception. Here nature inevitably becomes only a means towards achieving something else: aesthetic value, modernity, progress, or the future, wherein only humans benefit while nature gets nothing in return. Moreover, Otero’s insistence on breaking up ecological forces into elementary and isolated blocks like wind, water, and sunlight, which only then become the energies that animate his sculptures, bespeaks a conception of nature as subordinated to human perception and devoid of the messy characteristics of both ecology and history. The Torre Solar, more than the spectacle of a fully restituted nature, produced the image of a society being moved by its forces, but only after they had been effectively captured through the aesthetic and technological possibilities of Otero’s aesthetic machines.

Cinetismo and Geopower in the Web of Life

More than a neatly formed concept, geopower remains a compelling prospect for cultural analysis. The case of cinetismo provides insights into how geopower relies not only on practices of techno-scientific control but equally on the powers of aesthetics, including nonrepresentational forms like abstract art. As a cultural movement that developed across a variety of individual projects, institutional platforms, and urban spaces, cinetismo was part of the repertoire of strategies employed by the state to harness the forces of nature (and not only of petroleum). In general, these ideas implied that the forces of nature were at the disposition of humans and the state and that achieving modernity depended on harnessing their power through technological development. Such notions and cultural products help to explain how and why the works of Cruz-Diez and Otero took over the national landscape. As it proliferated, this bundle of artworks, cultural artifacts, and meanings provided ample opportunities for the symbolic reworking of the relations between society and nature during a period of intensive ecological transformations. By fulfilling a key role in the construction of such agreements, cinetismo became a force in the mutually constitutive transformations of culture, ecologies, and state-capital configurations.

In this article, I exposed the twofold nature, at once material and symbolic, of processes of environmental transformation. On the one hand, the Guri Dam was itself a cultural device. If it was able to remake the relations between nature and nation, it was largely because of its symbolic weight in a modernization narrative premised on harnessing the energies of the earth as the only way to catch up with the developed world or what we today would call the Global North. On the other hand, the aesthetic achievements of the works by Cruz-Diez and Otero were only possible because cinetismo developed through built space and owing to the public’s collective participation. Cruz-Diez hoped that the experience of pure color would reprogram the habits and senses of spectators, leading society to new levels of freedom. However, the definitive achievement of his aesthetic project (and of his theory of color) was dependent on a universalized notion of modernity as an accomplishment of environment-making through projects such as Guri, which entailed the subordination of nature (and of society) to the ebbs and flows of oil-funded urban development. Otero’s Torre Solar, its absolute optimism for the future—expressed both in the rhetorical machinery around the artist and the aesthetic machinery of his artworks—, functioned as a device to stitch back together what the state’s violent intervention in Guayana had sliced apart.

Nevertheless, it cannot be fairly argued that cinetismo was simply the outcome of a master project of the state. As tempting as it may be to reduce it to a mere political tool, I have shown that the relationship between cinetismo and the state often worked both ways. If kinetic art was shaped by the state’s environmental projects, it also attained the status of agent of ecological transformation as artists like Cruz-Diez and Otero developed their artistic projects, many times free from external ideological impositions due to a relatively pluralistic social-democratic consensus. In other words, their privileged position within the state-nature-culture nexus allowed kinetic artists to find spaces of agency, even when this agency ended up bolstering the power of the state over nature and society. Cinetismo thus provided not a flashy distraction from the systemic social and economic failures of the oil state, but was itself an active force in the environmental project of Venezuelan modernity, wherein both cinetismo and the Guri Dam were products of the same way of seeing that envisioned a future dependent on capturing of the forces of the earth.

- First called Represa de Guri, in 1974 the dam was renamed Central Hidroeléctrica Raúl Leoni. This was later changed in 2006, during the government of Hugo Chávez, to Central Hidroeléctrica Simón Bolívar.

- “…donde apenas hace un siglo nada había, sino leyendas, bosques, ríos y mitos.” Alfredo Boulton, El arte en Guri (Caracas: Macanao, 1988) 63, 26.

- Such as art critic Roberto Guevara’s Arte para una nueva escala (1978), published by Maraven (a subsidiary of the state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela), and Alejandro Otero’s Saludo al siglo XXI(1989), published by IBM.

- Some examples are the documentaries Carlos Cruz-Diez: En el camino del color (1971) by Luis Armando Roche, El artista y la ciudad (1976) by Mario Abate, and Cruz-Diez: El ilusionista del color (1978) by Manuel de Pedro.

- Additionally, frequent events, forums, and exhibitions at the Galería de Arte Nacional and Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Caracas, the Jesús Soto Museum of Modern Art in Ciudad Bolívar, and abroad, helped to solidify cinetismo as the most prominent artistic style in Venezuela during the 1970s.

- Marta Traba, Mirar en Caracas: Crítica de arte (Caracas: Monte Ávila, 1974) 126.

- Traba, Mirar en Caracas 129.

- Mirar en Caracas 123.

- See Mónica Amor, Theories of the Nonobject: Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, 1944-1969 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016) 8; Lisa Blackmore, “Colonizing Flow: The Aesthetics of Hydropower and Post-Kinetic Assemblages in the Orinoco Basin,” Natura: Environmental Aesthetics After Landscape, eds. Jens Andermann et al. (Zürich-Berlin: Diaphanes, 2018) 195; Sean Nesselrode Moncada, “Oil in the Abstract: Designing Venezuelan Modernity in El Farol,” Hemisphere: Visual Cultures of the Americas VIII (2015) 58; Luis Pérez Oramas “Notes on the Constructivist Art Scene in Venezuela (1950-1973),” Cold America: Geometric Abstraction in Latin America (1934-1973) (Madrid: Fundación Juan March, 2011) 54; and Megan Sullivan, “Alejandro Otero’s Polychrome: Color Between Nature and Abstraction,” October 152 (2015) 62.

- Jason W. Moore, “The Capitalocene Part II: Accumulation by Appropriation and the Centrality of Unpaid Work/Energy,” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45.2 (2018) 237-279; Christian Parenti, “Environment-Making in the Capitalocene: Political Ecology of the State,” Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, ed. Jason W. Moore (Oakland: PM Press, 2016) 166-184.

- Jason W. Moore, “The Value of Everything?: Work, Capital, and Historical Nature in the Capitalist World-Ecology,” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 37.3-4, (2014) 251. The concept of work/energy expresses the continuity between human and extra-human capacities to do (exploited or outright appropriated) work. Inspired by Richard White’s classic environmental history account of the remaking of the Columbia River, Moore introduces this notion in order to “pierce” the Cartesian divide between humanity and nature. It is a fundamental part of Moore’s understanding of capitalism as a world-ecology made of nature, capital, and the state. See Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (New York: Verso, 2015) 14-18.

- Daniel Hartley, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, and the Problem of Culture,” Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, ed. Jason W. Moore (Oakland: PM Press, 2016) 162.

- Sharae Deckard, “Latin America in the World-Ecology: Origins and Crisis,” Ecological Crisis and Cultural Representation in Latin America: Ecocritical Perspectives on Art, Film, and Literature, eds. Mark Anderson and Zélia M. Bora (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2016) 17.

- Chris Campbell and Michael Niblett, “Introduction: Critical Environments: World-Ecology, World Literature, and the Caribbean,” The Caribbean: Aesthetics, World-Ecology, Politics, eds. Chris Campbell and Michael Niblett (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016) 5.

- See Jason W. Moore, “The Capitalocene Part II: Accumulation by Appropriation and the Centrality of Unpaid Work/Energy,” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45.2 (2018); Christian Parenti, “Environment-Making in the Capitalocene: Political Ecology of the State,” Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, ed. Jason W. Moore (Oakland: PM Press, 2016); Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History, and Us (New York: Verso, 2016) 87-96; Timothy W. Luke, “On Environmentality: Geo-Power and Eco-Knowledge in the Discourses of Contemporary Environmentalism,” Cultural Critique 31 (1995), 57-81; Gearóid Ó Tuathail, “At the End of Geopolitics? Reflections on a Plural Problematic at the Century’s End,” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 22.1 (1997) 35-55; Federico Luisetti, “Geopower: On the States of Nature of Late Capitalism,” European Journal of Social Theory 22 (2018) 342-363.

- Moore, “The Value of Everything?” 251.

- Moore, “The Capitalocene Part II” 245.

- Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (New York: Verso, 2015) 14.

- Jason W. Moore and Raj Patel, A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017) 179.

- Bonneuil and Fressoz, The Shock 62.

- “On Environmentality” 76-80.

- Bonneuil and Fressoz, The Shock 90. Contrary to the idea of ecology or world-ecology, the “environment”—especially when used in the context of policy and state powers—is not a horizontal system of interdependent relations, but rather is “organized centrally, around a given focal point” and “reserve[s] a particular ontological position for human beings.” Andreas Broeckmann, Machine Art in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016) 224.

- Moore and Patel, A History 179.

- Moore, Capitalism 193.

- With the possible exception of Elizabeth Grosz, who has used the term geopower to define art as “an extraction and harnessing of the dynamic forces of the earth” through which chaotic matter is made to appear as sensation. Grosz et al., “An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, Inhumanism and the Biopolitical.” Theory, Culture & Society 34 (2017) 132-137. However, Grosz does not engage with specific instances of geo-managerialism, resource extraction, or environment-making, but rather concentrates on elaborating a posthuman ontology of art.

- Pérez Oramas, “Notes” 55.

- Juan Ledezma, “The Sites of Abstraction: Notes on and for an Exhibition of Latin American Concrete Art,” The Sites of Latin American Abstraction, ed. Juan Ledezma (Miami: CIFO, 2008) 34-39.

- Alexander Alberro, Abstraction in Reverse: The Reconfigured Spectator in Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017) 3.

- Fernando Coronil, The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela (University of Chicago Press, 1997) 237.

- In fact, it was the plans for the development of heavy industries in Guayana, in particular the aluminum and steel sectors, that generated the need for cheap hydroelectricity in the first place. A. Curtis Wilgus, ed., The Caribbean: Venezuelan Development (University of Florida Press, 1963) 84. The Orinoco Steel Mill (Sidor) was one of the main beneficiaries of low-cost electrical energy drawn from the Caroní river. Additionally, one fifth of Guri’s electrical energy output went to local aluminum production in the form of heavily subsidized hydroelectricity. Patrick McCully, Silenced Rivers: The Ecology and Politics of Large Dams(London: Zed Books, 2001) 254. The mixed company Caroní Aluminum Corporation (Alcasa) had the mission to expand into the export markets after satisfying national demand (Wilgus, The Caribbean 187).

- Max Haiven, “The Dammed of the Earth: Reading the Mega-Dam for the Political Unconscious of Globalization,” Thinking with Water, eds. Cecilia Chen, Janine MacLeod, and Astrida Neimanis(Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013) 215.

- Haiven, “The Dammed” 216.

- Raúl Leoni et al., Discursos con motivo de la inauguración de la Presa de Guri, (Caracas: Editorial Arte, 1968) 32-33.

- “Todo ese mundo de vida vegetal, de fuerza primaria, de misterio de selvas, de boas y de ecos cataclísmicos; todo ese hechizo se detiene, de pronto en la mansa orilla, ya vuelta lago, frente a la gran Represa … Así, como sucedió el primer día del universo, es también así la creación de un nuevo país, de una nueva Venezuela.” Boulton, El arte en Guri 24-26.

- Carlos Cruz-Diez, Reflexión sobre el color (Caracas: Fabriart, 1989) 52.

- Ariel Jiménez, Carlos Cruz-Diez: The Autonomy of Color (Texas: Cruz-Diez Art Foundation, 2017) “A Constant Struggle”, “Chromosaturation.”

- Cruz-Diez, Reflexión sobre el color 52.

- El arte 64, 70-72.

- Alfredo Boulton, “El color en Cruz Diez,” El Nacional, Feb 16, 1972, B-1.

- Carlos Cruz-Diez and Ariel Jiménez, Carlos Cruz-Diez in Conversation with Ariel Jiménez / Carlos Cruz-Diez en conversación con Ariel Jiménez (New York: Fundación Cisneros, 2010) “The Liberation of Color.”

- “Obras de Alejandro Otero y Cruz Diez se inauguran en Guri,” El Universal, Nov 8, 1986, 4-1.

- Coronil, The Magical State 168.

- “Sus reflejos metálicos, sus movimientos conjugados con el sol y con el viento, tienden a restituir la gracia, la transparencia, la luminosidad del río, hoy subterráneo en ese lugar.” “Obras” 4-1.

- Teresa Alvarenga, “Las últimas obras de Alejandro Otero,” Imagen 72/73 (Nov 1972) 9-10.

- José María Salvador, “Alejandro Otero: Memorabilia, 1993,” Alejandro Otero ante la crítica: Voces en el sendero plástico, ed. Douglas Monroy (Caracas: ArtesanoGroup Editores, 2006) 238.

- Juan Acha, “Luz, espacio y movimiento de Alejandro Otero, 1976,” Alejandro Otero ante la crítica: Voces en el sendero plástico, ed. Douglas Monroy (Caracas: ArtesanoGroup Editores, 2006) 153.

- “…el más alto monumento a la gloria del Caroní.” Boulton, El arte 26.

- Leo Bersani, The Culture of Redemption (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990) 1.

- Bersani, The Culture 1.

- “Obras” 4-1.

- Bonneuil and Fressoz, The Shock 90.