We Need Hope

We need hope. I do not need to recount the reasons. We each know the litanies. We all know the threats.

Phillip E. Wegner’s book participates in the project we call theory, utopia, and reading each for the sake of hope. Wegner explains and historicizes hope in a deeply personal manner. What I mean by personal in this context could be mistaken to indicate idiosyncrasy on the part of the author. The book relies on what he describes as a “disposable canon” (16). Wegner situates his selection of interlocutors, “While I am convinced that the close and creative reading of all the texts I engage with in these pages is a valuable education in its own right...I hope that the discovery of the motivation of these choices becomes another occasion for intellectual delight as well as teaching” (16). What could he mean? Well, in the book’s structurally focused latter half, Invoking Hope swings from W.E.B. DuBois’s John Brown (first published in 1909) to Karen Blixen’s story “Babette’s Feast” (published under the nom-de-plume Issac Dinesen in the June 1950 issue of Ladies Home Journal) and then again on to the Adam Sandler-Drew Barrymore flick 50 First Dates (2004) and Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2312 (first published in 2012) only to conclude with David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (first published in 2004). The heading “Utopia” introduces this half of the book, and utopias have long been, well, idiosyncratic. We all know the adage, one person’s utopia is another’s immiseration. Still, for me, the work of the personal in Wegner’s book can be traced to his commitment to maintaining an idiom consistent across his works. Wegner harvests his explanatory mode from the works of Badiou, Barthes, Bloch, Lacan, Jameson, and others. He plants and tends a deeply thought garden of expression across his ongoing project of thought and writing. Call it an oeuvre or life’s work, if you will, but in the age of the media conglomerate franchise I have come to think of it as the Wegnerverse.

Let me explain.

First, Wegner’s work has never shied from popular culture, nor from genre writing in his analysis. As a graduate student, for instance, I learned about the possibilities of the Lacanian quilting point from Wegner’s insightful periodization of The Terminator (1984) and Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991) across the symbolic first death of the Cold War (see Life Between Two Deaths: U.S. Culture, 1989-2001): the unstoppable, emotionless threat represented by the machine in the first film transforms into a a big, lovable father-figure of a machine in the second. Wegner’s investment in theory and continental philosophy does not preclude his curiosity in popular culture.

Second, Wegner’s commitment to the project of theory exceeds any one master signifier in the field. As he suggests at the outset of Periodizing Jameson: Dialectics, the University, and the Desire for Narrative, we need to add a synthetic practice to the declaration “Always historicize,” namely “Always totalize” (31): a practice that is not only structurally minded, but historically attendant. The first half of Invoking Hope follows the heading “Theory” and demonstrates Wegner’s capacity to blast, smite, and transcend theoretical interventions, historicizing them and drawing them together into a larger structural arrangement. Such a perspective emerges through Wegner’s critique of the university. Here Lacan’s three orders meet Greimas’s semiotic square, as repurposed by Jameson. Wegner concedes that he does the heavy lifting for this explanation in Periodizing Jameson (Invoking Hope 40): readers familiar with that title will keep up here.

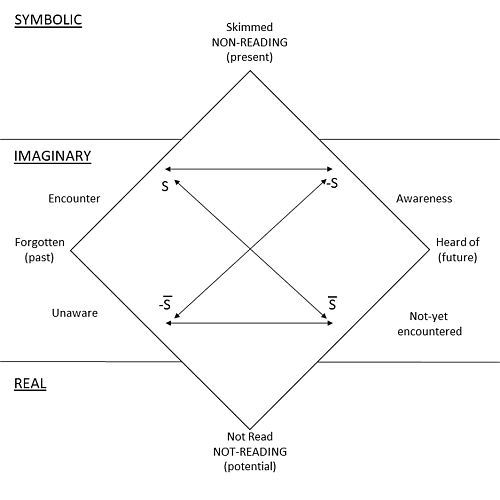

Third, there is a shared language across Wegner’s texts. Invoking Hope participates in the Wegnerverse from its chapter design down to its sentences that grows out of the theory. I think the best example of how Wegner uses this transcoded structural device of the Greimassian semiotic square can be found in chapter 2, “Toward Non-Reading Utopia” where Wegner takes up Pierre Bayard’s How to Talk about Books you Haven’t Read (2007). The opposing terms here are “encounter” and “not-yet encountered” and the determining contradiction is “awareness” and “unaware.” Put succinctly, there are books we have forgotten and books we have heard of, book we are skimming and books we’re not reading (skimming here has to do with Bayard’s claim and Wegner’s elaboration that nonreading exposes the truth: we never really read a book, we always, to some extent, nonread it). I happen to find the semiotic square much more legible than an all too quick description of it, so here you are: a semiotic square layered with Lacan’s three orders to represent the possibilities of non-reading (73).

Here the encounter with the symbolic neatly fits with the act of reading in the present (thank you for nonreading this review!). The imaginary is the demesne of those books we’ve forgotten or transposed into our generalized understanding and of those books we know we ought to take a look at or a listen to. Finally, the realm of the real is one of where possibilities reside: which titles are we unaware of and have not-yet encountered?

Fourth, you don’t need to read each entry to benefit from the larger project (sorry Phil!), which is, from the work of Bloch, to train our desires! In a sense, Wegner endorses non-reading in the way Bayard would have it: “all ‘reading is first and foremost non-reading’ (23; qtd. in Wegner 71). Along with Bayard, Wegner pushes the utopian horizon of non-reading by allowing it to modify what we consider reading in the first place. He explains, “any communication we offer of a book, verbal, written, or otherwise, is a locally and deeply contingent act of writing that book.” Crucially, he adds, “this is the case even if such writing takes place in our heads and only for the audience of our future selves” (74) — Wegner adds a whole new meaning to honeycomb universes, in this case they are the honeycombing vertiginous iterations of readings, some deeply personal github only accessible through conversation, gesture, reading, and writing. I tell my students that writing and thinking happen at once. The reconsideration of reading itself inspires an update to the axiom: “All reading is writing and all writing is a creative act” (13).

These points may help to justify or explain my own encounter with Wegner’s invocations as a massive, sprawling project that stretches across time and space. Grounded as it is in institutional history, I find Theory and Utopia for Dark Times to be sufficiently materialist in its refutation of post-critique. It encourages me to read a demonstration of criticism rather than, as Wegner offers in his introduction, a non-reading of post-criticism. It makes a case that finally converges in an argument for hope. Even if nonreaders struggle with certain chapters the overall project is worth it: both as a cohesive argument that undermines anti-political thinking and as a kind of proof for trusting and then explaining one’s intuitions about culture, theory, and utopia.

If none of this convinces you to read the book, let me try another approach for the literary historians. Wegner’s reading of W. K. Wimsatt Jr. and Monroe C. Beardsley’s “The Intentional Fallacy” (1946) and “The Affective Fallacy” (1949) as a Badiouian event in the history of the Anglophone university is a worthy reconsideration of dialectical thinking and how to position literary criticism within the academy that spurred a diversifying generation of students well-equipped with the capacity to close read (56). Nonreaders curious about critical university studies, Plato’s The Republic, Badiou, and new criticism will be interested in skimming this chapter.