Towards a Renewal of Israeli Marxism, or Peace as a Vanishing Mediator

The Israeli political left has been in deep crisis for over a decade, shrinking by now to virtual non-existence.1The onset of this crisis is usually traced back to the eruption of the second intifada, or armed Palestinian resistance, which signaled the unofficial end of 1990s peace-making era, dragging into deep existential crisis a political left for which “peace” named not only a historical goal but also an intricate utopian imaginary. Former Israeli Prime minister Ehud Barak’s declaration following the 2000 Camp David talks that “there is no partner for peace” seems from today’s vantage point to have performatively buried peace as a political goal. No matter what one thinks about it today — that Israel was never serious about achieving it; that it is still being pursued by one or both sides; that it was never achievable in the first place — it is clear that peace has disappeared from the landscape of Israeli politics as a goal behind which a left could unite, or as a concept flexible enough to accommodate many Israelis’ hopes. Instead, peace has become a permanent feature of the Israeli political system, to which all Israeli political parties are in principle committed, a kind of permanent spot at one’s political peripheral vision to which not much attention is given anymore. The grand historical goal and its accompanying temporality and utopian horizon have been replaced by a kind of permanent securitization, the constant terrorizing or pacification of the Palestinians by Israel, the horrors of which are explored extensively in, for example, Eyal Weizman’s writing.2 The resulting temporality of Israeli reality can be characterized as what Eric Cazdyn calls “chronic time,” from which the possibility not only of cure but that of death itself have been removed, generating a homogeneous, predictable, alternative-less present.3

It is this vanishing of peace as an effective goal from the landscape of Israeli politics that will concern me in this essay. The renewal of the Israeli Left stands or falls precisely with the way we narrate this disappearance of peace, to which we have already mentioned a number of unsatisfactory responses: to argue that Israel never truly pursued it; to abandon it as an unachievable dream; and to ignore it altogether, focusing instead on “social” issues. To these we can add now another more recent response, which seems to characterize some of the Marxist or socialist viewpoints. Namely, that the pursuit of peace was only a convenient illusion, under whose cover Israeli society was thoroughly neoliberalized, with very little resistance. The privatization of previously state-owned or controlled institutions, including education, health, communication and others had massively accelerated in Israel in the late 1980s, only a few years before the Peace Process started, and it has continued uninterrupted throughout the 1990s.4 Excellent commentators such as Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, Dani Gutwein, and more recently Eran Kaplan, have tended to see the peace process as nothing but a convenient front for dismantling the Israeli welfare state.5 In Gutwein’s account, on which I will have more to say in what follows, peace as a political project ends up simply being a cover for pursuing material middle-class interests, which for him align with neoliberalization.

This last approach to peace as a political goal has the merit of situating the Peace Process within a larger process social transformation. However, the resulting narrative seems to be that which critics usually denounce as so-called vulgar Marxism, in which superstructural tendencies are seen as mere reflections or expressions of the truly determining instance — the economic base or infrastructure. Nor is this foray into vulgar Marxism new to the Israeli Marxist thought. Another clear case is Tamar Gozansky’s The Formation of Capitalism in Palestine (1986), one of the most important Hebrew sources (if not the most important) for anyone who wishes to understand the historical emergence of capitalism in the area. In the book, Gozansky takes a similar stance with regards to the pre-state collectivist Zionist settlements — treating their revolutionary pathos and imaginary as nothing but petite-bourgeois ideological cover for the hidden, real economic process, namely the establishment of the conditions for capitalist accumulation.6 Gozansky’s account here finds an unlikely ally in non-Marxist analyses of Zionism from the 1980s and 1990s, such as Zeev Sternhell’s, in which Zionist socialist aspirations are seen as convenient cover for colonialist nation-building.7 We will touch further on the interpretation of Zionism much more extensively in what follows. For now, it is important only to register that the narrative in which the Peace Process is simply a cover for neoliberalization reduces that process to an agentless reflection of economic processes, and its believers to dupes.

Dissatisfaction with this “vulgar-Marxist” account of the peace process demands that we try to modify it. The first part of this essay constitutes an attempt to suggest one such narrative modification of our account of the emergence and disappearance of peace as a political goal in Israel. But a short note about the explosive issues on which this essay touches is in order at this point. Positions regarding Palestine/Israel tend to be strongly entrenched. As a result, any mention of the subject must conspicuously signal its belonging to this or that camp, or it risks immediately coming under the suspicion of actually belonging to the ranks of the enemy (knowingly or not) and is received with very little patience. This lack of charity is perhaps exacerbated by the crisis of the humanities and social sciences academia, which tends to form academic subgroups suspicious of each other where once there was a wider collective project. I would therefore like to emphasize that I have no intentions here to rehabilitate Israeli nationalism, or to stage a defense of it, or to deny the oppression of Palestinians at the hands of Zionists and later the state of Israel. So I hope the following can be seen not as a sinister attempt to rehabilitate what we rightly reject, but rather can be considered an earnest attempt to challenge the mainstream Leftist view of Israel and its history. Given the decline of any Leftist project in Israel — compared to the 1990s — I hope such an attempt can be tolerated and deemed acceptable in principle, even if one remains unconvinced of its conclusions. As I hope will become clear, Leftist convictions about the colonial violence that were (and are) an inseparable part of the Israel’s history and present, are very much preserved and reaffirmed in this attempt to challenge this mainstream narrative.

And I should use this opportunity also to note the limitations of the following argument. I will here be considering the rise of post-Zionism and the pursuit of peace as political forces within Israeli society. My points of reference — both intellectual and political — will be almost entirely Israeli, and my conclusion about the historical function of these will hold only for that context. The history of Israel considered from an American vantage point, and the international Leftist stance towards Israel, remain outside the scope of this paper. Surely, Israel and its history hold a very different function in the non-Israeli context (one that has to do with an estranged attempt to think our own non-Israeli situation, in a Brechtian or Darko-Suvin-like manner). I will not in this essay be able to explore this more international perspective. That an essay internal to the Israeli imaginary should appear in English and outside Israel is another matter worth discussing at a different opportunity. Another limitation is the narrowing-down of the scope of post-Zionism to positions articulated explicitly in relation to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, which is a limitation common to many discussions of post-Zionism but that is nonetheless problematic. I will not be able to expand the scope to include positions that echo post-Zionist critiques in areas such as the Mizrachi counter-narrative to Israeli national hegemony (whose most well-known academic representative is perhaps Ella Shohat); or ones centered around a critique of religious identity (as in Daniel Boyarin’s writing); or any other post-Zionisms which center on other identity categories. The expansion of the argument below to these other varieties is not difficult to make (for the points of criticism raised hold true in these cases too), but I will not be able to do so explicitly in this essay.

The new narrative will have the advantage of not reducing peace to mere ineffectual illusion, while simultaneously leaving intact its relation to the transformation of Israeli capitalism. It is this modification that will allow me to suggest the contours of a new interpretation of Zionism and Israeli nationalism, one that could prove productive for a renewal of the Israeli political Left (while retaining the urgent goal of Palestinian liberation). The theoretical framework that will help me offer this new narrative option for the rise and fall of peace is that of the vanishing mediator, first developed by Fredric Jameson in his essay on Max Weber and the rise of Protestantism, generalized and elaborated later by Slavoj Žižek.8 Jameson’s formulation allows us not only to avoid both the vulgar “materialist” account of historical transformation and the idealist one (namely, that history is simply the realization of certain ideas). It also, as Žižek emphasizes, suggests that the pursuit of the goal that ends up vanishing (in our case, the political pursuit of peace) is a step without which the neoliberalization of Israel could never have been achieved.9

What I will try to show is that the pursuit of peace happens to follow the vanishing mediator narrative form. Narratives that unfold according to the vanishing mediator form advance along two axes: means and ends, or infrastructure and superstructure (to use the Marxist vocabulary). The narrative form here has three distinct moments: the first is an explicitization of older ends — ideological goals of the previous system that are suddenly thrown into sharp relief. In the next moment, new means are elaborated in order to achieve this older goal, replacing older means which seem to have failed to serve their purpose. In the last moment, the older goal itself vanishes, leaving us with the new means, a new socio-economic infrastructure. In Jameson’s essay, whose subject matter is the rise of Protestantism and its relation to the “infrastructural” formation of capitalism, the first moment is that of Luther (in which the older religious goals are stressed and the existing means condemned); the second one corresponds to Calvin (in which the new rationalization of means is elaborated), and the third — in which religious goals disappear altogether, leaving us with nothing but the new means or infrastructure, capitalist social relations — is simply modern society. It is in these moments of historical transformation that the effectiveness of the superstructure is revealed, or as Jameson puts it: “Thus, the superstructure may be said to find its essential function in the mediation of changes in the infrastructure… and to understand it in this way, as ‘vanishing mediator,’ is to escape the false problems of priority or of cause and effect in which both vulgar Marxism and the idealist position imprison us.”10

It is important to emphasize that I am not here elaborating some immutable historical law according to which all change takes place. My claim is much more modest: that it is easy to narrate the pursuit of peace in 1990s Israel according to the vanishing mediator schema, and that this narrative option solves all kinds of problems that exist in other narrative options, some of which I discussed above. But the purpose of this essay is not merely to offer a new narrative for the pursuit of peace and its disappearance. Rather, I also aim to show that this new understanding of the peace-making years can transform our understanding of our own present, as I will elaborate later.

The new narrative of the rise of peace that I am suggesting starts with the emergence of peace as a political goal for the Israeli Left. It is important to notice, for our purposes, that “peace” is not a completely new goal to Zionism and Israel. Rather, it comes up marginally in the history of Israel. We can trace peace as a goal to the peace talks that took place after the 1948 war, and even further back into the pre-statehood years and the different attempts to reach an agreement between Zionists and Palestinians over political control of Palestine and immigration into it (including proposals for the division of Palestine, but also more forgotten ones for establishing a bi-national state).11 And even further back: peace is (imaginarily) achieved in Herzl’s 1902 utopian novel Altneuland almost as a bi-product of syndicalist or socialist-utopian social form of the new utopian society in Palestine.12 Crucially, in all of these earlier cases peace was a goal subservient to a larger collective project, and not the primary political aim in its own right.

One can argue that peace reemerges as a leading goal only in the 1980s, with the “Peace Now” movement coming into the center of public consciousness after the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon (which culminated in Israeli cultural memory in the mass protests that followed the massacres in the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps). It is at that moment that the old goal of peace suddenly comes into sharp relief, becoming a collective goal in its own right, a sine qua non of achieving any other national goal — in short, an unshakable political prioritization of “choosing the path of peace,” as it was put in the officers’ letter that founded Peace Now.

This way of narrating the emergence of peace as a political goal in Israel fits perfectly with the first moment of the vanishing mediator narrative structure. To repeat, in this moment, an old peripheral goal is reasserted with greater force, accusing the older way of doing things of not pursuing it efficiently. The Israeli protests following the massacres and the emergence of Peace Now fit the bill perfectly.

The reemergence of peace as a political goal was followed by the invention of new means to achieve this goal, after having denounced older attempts to achieve it as ineffective. This new way of pursuing peace is invented in the late 1980s. What takes place is essentially a denationalization of the way peace is to be pursued: its freeing from what was hitherto seen as “Zionist,” ending its mediation by the institutional framework of the state. Denationalization should be taken here as a transcoding term (much like “rationalization” in Jameson’s vanishing mediator narrative form), since it operates on two levels simultaneously: first on the level of the purely economic — in which it designates the onset of deregulation, privatization, and the demise of state-led capitalist development in Israel after the 1980s. And secondly on the level of knowledge production—where the older system of national knowledge is to be interrogated and revised (if not altogether exploded) in order to facilitate the production of knowledge that will better facilitate the achievement of peace. It is here that we will have to consider the Israeli intellectual trend usually known by the name “Post-Zionism” as that which forges precisely this kind of new knowledge. Post-Zionism is usually associated with the writing of the so-called Israeli New Historians and critical sociologists, such as Benny Morris, Ilan Pappé, and Uri Ram. It is in their writing that the Israeli national narrative, or the “Zionist metanarrative” as Gershon Shaked calls it, comes under scrutiny.13 The national interpretation of Israeli past comes under fire here from all directions, as Laurence Silberstein’s extensive survey emphasizes: the national story according to which Zionism is a peace-loving liberation movement is replaced by its reading as a colonial enterprise; The oppressive nature of the nation building project—towards Palestinians, Mizrachi Jews, Women, and other groups replaces in their account the myth of the national melting-pot. Most importantly for my purposes, the Post-Zionists insisted on the historical failure to achieve peace by national means, constituting a kind of utilitarian rejection of Zionism which is only later succeeded by condemning Zionism morally, as Silberstein and recently Kaplan emphasize.14

Benny Morris’s 1988 brief essay in Tikkun, considered sometimes to be a founding document of the Israeli New Historiography, can be taken as exemplary of this utilitarian condemnation of Zionism and the Israeli nation for their failure to achieve peace. Morris briefly outlines the research programs of the New Historians, emphasizing their explosion of the Israeli national narrative, indicting the national leadership for a “general lack of emphasis on achieving peace” after the 1948 war.15 Opposite the national narrative, Morris concludes:

The New History is one of the signs of a maturing Israel… What is now being written about Israel’s past seems to offer us a more balanced and truthful view of the country’s history than what has been offered hitherto. It may in some obscure way serve the purposes of peace and reconciliation between the warring tribes of that land.16

It is here that Morris enacts a kind of reconciliation of morality — truth-telling and scientific objectivity — with a utilitarianism whose aim is peace. The New History according to Morris both usurps the ethical stance usually claimed by older national historiography, and simultaneously provides us with a narrative that is better at facilitating the achievement of peace.

This denationalization of knowledge for the goal of peace can be detected in many of the writings of the Post-Zionists. In the introduction to their 1994 Palestinians: The Making of a People, Israeli sociologists Baruch Kimmerling and Joel Migdal explicitly tie the scholarly purpose of the book — to provide a socio-historical account of the emergence of the Palestinian nation since the early nineteenth-century — to an effort to “view the Palestinians not as anthropological curiosities, but as social group deeply affecting the future of the Jews,” the acknowledgment of which has a clear purpose:

Hovering behind all this work has been an awareness that mutual Jewish-Palestinian denial will disappear slowly, if ever. Still, recent events have made one thing clear: The Palestinian dream of self-determination will likely be realized only within the assent of a secure, cohesive Israel, and the Israeli dream of acceptance throughout the Middle East will likely need Palestinian approval.17

The reconciliatory purpose of the volume, even if not explicitly stated, is clear, as well as the accusation that previous (national) knowledge or recognition of the Palestinian “other” is tantamount to outright denial of its existence.

With the example of Kimmerling and Migdal’s book we have already imperceptibly moved from a denationalization of knowledge in a more negative sense — the debunking of the national narrative highlighted in Morris’s essay — to a more positive one that involves the production of an alternative form of knowing, one whose making does not occur solely within the confines of national institutions. It is not pointless to note that Kimmerling and Migdal emphasize in their introduction that the book is a result of many years of working alongside Palestinians outside the usual academic institutional setting for Israeli academics; nor is it purely accidental that the work of the prominent New Historians, especially in its early stages, was produced in academic institutions outside Israel, as Silberstein reminds us. The exact point is that the site of peacemaking is not the national institutional framework. Thus the relation to the Palestinian other is no longer to be invented and managed within national institutions (universities being part of that institutional framework). Rather, this mediating structure is to be dissolved and a (seemingly) less mediated, more direct, relation is to be formed. It is not a coincidence that in this period first-hand accounts of interacting with Palestinians, such as David Grossman’s The Yellow Wind became huge successes.18 What Žižek sees as the intensification of the older superstructure in this second moment and what Jameson sees as the freeing of rationalization to take root outside the monasteries everywhere in the social structure under Calvinism is precisely what takes place when peace-making becomes something to be pursued outside the institutions of the Israeli state — which is to say, everywhere.

Inseparable from this denationalization of the means of peacemaking is the transition from a utilitarian approach — seeing the older means as ineffective — to a much more personalized ethical commitment to the production of denationalized knowledge. The imagined relation to the Palestinian other is no longer to be mediated by nationally-produced knowledge; rather, every subject is responsible for producing this knowledge: noticing the everyday repressed expressions of the oppression of Palestinians in Israeli reality; knowing local histories of Palestinian deportation and expropriation alternative; reading the landscape for signs of past Palestinian dwelling — all of these become part of an individualized ethical commitment to peace, which we will not be able to address extensively here. The well-documented debate between Morris and Ilan Pappé revolves precisely around this point. While for Morris the ethical task of the New Historians stands or falls with their adherence to objective positivist truth, for Pappé the acceptance of alternative narratives into one’s own becomes a moral obligation that comes before any objective search for empirical truth (which is by no means abandoned by Pappé, as others argue).19 It should be clear how different Pappé’s narrative relativism is from that proliferation of narratives whose origin is postmodernism’s incredulity towards metanarratives, to adopt Lyotard’s terminology: the former is still working in the service of a clear metanarrative. The common association of Post-Zionism with postmodernism is therefore too hasty and inaccurate, as others comment.20 Instead, we should see Post-Zionists’ opening up of the field to alternative perspectives as at least somewhat different than the postmodern one, since the former’s “relativism” is simply a clearing of the way, the initial action on which the creation of a new historical goal is premised. The postmodern freedom from history or sheer multiplicity of narratives is therefore only a first moment in Pappé’s own thinking—exemplified by the linear, closure-producing narrative of books such as The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine.21 Pappé’s position ends up elaborating a whole private ethics, a code of personal conduct, that should be adopted by anyone that shares the goal of peace — an ethical position that is “free” from the mediation of national institutions of knowledge production.

Yet it is not only knowledge production or new personal ethics that constitute this grand denationalization of means. We should also register, however briefly, the ways in which denationalization operates on the level of social form itself. Again — one should not look here for an explicit connection between peace and neoliberal commitments or goals. Rather, what is crucial here is the Post-Zionist assault on anything that has to do with state institutions in the name of peace, which then sets the stage for the private market to take over what was once mediated by the state alone. Important in this regard is the critique of Israeli housing, health, national broadcasting, job placement, education, and all other welfare-state services and determinants of social life. Thus, the connection forged by critical Post-Zionist sociological studies always emphasizes that the Arab-Israeli conflict is not simply an external circumstance or condition to which Israeli society must respond, but that it is rather “constitutive of the Israeli political-social order” itself, to quote Yagil Levy and Yoav Peled, two prominent voices within Post-Zionist sociology.22 Levy and Peled’s critique of functionalist Israeli sociology is a thinly-veiled critique of Israeli national sociology:

What Israelis usually refer to as “the conflict” is viewed by functionalist scholars as essentially external to the Israeli social-political order. The conflict is rooted, they believe, in regional international circumstances encountered by the Zionist project, both before and after 1948. Thus they have never undertaken an etiological study of the conflict, which would examine its development in conjunction with the evolution of the Israeli social order, and the mutual conditioning of the two. Rather, what functionalist research has done is look for the effects of the conflict on Israeli society, which is seen as only reacting to it as an external force.23

To see the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as the totalizing kernel of all Israeli social reality is therefore the centerpiece of post-Zionist sociology — one through which the failure to treat all social evils can always be related to this conflict, or be its internal social expression. It is on this connection that peace as a utopian imaginary hinges: its achievement becoming a condition for reconciling all other social antagonisms.

Perhaps the most important connection between the conflict and the internal workings of Israeli society is the one that has to do with forging a new conception of the function of the military in Israeli society. Sociologist Baruch Kimmerling’s writing on Israeli militarism is of paramount importance. If the Israeli military has been viewed until the post-Zionists as the pinnacle of the national “melting pot,” successfully neutralizing previous social contradictions in producing national subjects, Kimmerling reverses the picture. In his account, the militarization of Israeli society means first and foremost that other social problems are left untreated as a result of the army’s primacy as social institution. This primacy of the military is naturalized, according to Kimmerling:

The important determinant factor here is whether or not the military mind turns into an organizing principle in ideological, political and institutional state realms, and whether or not strategic considerations (defined as ‘necessities’ to actual physical survival) become ascendant at the expense of all other considerations — Moshe Dayan summarized this situation with a turn of phrase when he explained at the start of the 1970s that ‘it is impossible to bear two banners at the same time’ — the reference is to the ‘security banner’ as opposed to the banner of social-welfare and other societal goals.24

Kimmerling’s quick overview of the structuring of Israel’s economy predominantly around the military’s needs is here meant to drive home his point about the primacy of military interests in Israel’s internal social structuring. The military’s role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict then provides us with the link between internal social strife and the external goal of peace. It is the nation under which this material and social commitment to the military is to be preserved, materially marginalizing all other social problems. National institutions come to signify the reproduction of social suffering, rather than the collective attempt to cure it. As we said before, we should not expect Kimmerling to recommend the privatization of the military, for “privatization” is a term already encoded with a notion of social change oriented towards a different goal. Rather, Kimmerling’s conception of the social role of the military — becoming in his account the reproducer of social problems rather than their cure — is a perfect attempt to denationalize the entire field of mediating social relations. Arguing for the need to roll back the state’s management of this or that social function, paves the way for pursuing neoliberal reforms with no little or no resistance. The much later privatization of military functions (that checkpoints between Israel and the West bank are manned by private security, but also increasingly the buying from the outside of many other functions that used to be internal to the military itself) has its origin precisely in this initial drive towards denationalization.

Importantly, we should notice that this denationalization, which follows the emergence of peace as a goal, fits perfectly within the narrative form of the vanishing mediator. As we mentioned initially, the second moment of this narrative form involves the elaboration of new means for achieving the goal that reemerged in the first moment. As I have tried to show, this is precisely what happens in the case of post-Zionism: elaborating denationalized means to achieve the goal of peace. It is here that the narrative I have been elaborating avoids seeing peace as simply a convenient illusion or sinister cover for pursuing privatization. Rather than simply being an illusion used to dupe the masses, the superstructural or ideological drive towards peace plays an effective role in the dismantling of the nationally-planned Israeli economy in accordance with Washington-Consensus neoliberalism — even as the peace movement misrecognizes its historical agency, as in the well-known examples of the Jacobins or Protestantism. As Žižek claims, the superstructural intensification that characterizes the second moment of the vanishing mediator should be seen as itself a result of the contradictions ripping apart the socioeconomic base — an intensification expressive of the fact that the old superstructure can no longer help contain these contradictions. It brings about the destruction of the old system, even as it still operates under its banners.25

The last event of the narrative that I am suggesting is nothing but the disappearance of peace as an effective goal from the landscape of Israeli politics, the narration of which was the goal set in the beginning of this essay. This element also fits nicely with the vanishing mediator narrative form, which ends, as I mentioned above, with the disappearance of the goal. The vanishing of the old goal whose reemergence set things in motion is evidence not of a failure, but of the success of historical agency of those who pursued it, of their effectiveness in enacting the transition to a new system. The disappearance of what Žižek calls (following Badiou) the contingent act that founded the new system — in this context, the political drive towards peace — is the sure sign of that political project’s success in exerting historical agency (even if not in the way it had imagined itself to do so).26

We can therefore narrate 1990s Israeli peacemaking as a vanishing mediator for the neoliberalization of Israeli society — the pursuit of an older goal that had been effective in bringing about, unintentionally, the transformation of social relations. This narrative of 1990s peacemaking in Israel is a more satisfying account of it than any of those that we briefly surveyed earlier. For here the pursuit of peace is not denied historical efficacy. Nor is its relation to material transformation denied. Finally, peace’s sudden disappearance or ineffectiveness is here admitted and accounted for. Yet this essay will remain somewhat of a sterile intellectual exercise if it ended here, with the simple demonstration that the pursuit of peace can be narrated along the lines of the vanishing mediator narrative structure. So one should now register that we have, perhaps without noticing it, allowed temporality to inflect what is accepted as a timeless truth by many on the Left: The Post-Zionist view of Zionism as a colonial or otherwise repressive enterprise. In the narrative I suggested above, this timelessness has been questioned. If Post-Zionism is to be viewed as the intellectual “branch” of 1990s Israeli peacemaking, it follows that its interpretation of Zionism had risen to serve the purpose of the peacemaking project. Thus, this post-Zionist narrative might be useless today after peace’s vanishing as a goal. That, then, puts us in a rather uncomfortable position if we continue to deepen and further elaborate the post-Zionist position (which should remind us that all abstract ethics tend to be the feeble remnants of collective projects). To be sure, viewing Zionism as an oppressive colonial force was not invented by Post-Zionist intellectuals. Yet the adoption of this interpretation as the political umbrella under which the Israeli Left is to be united (and that more or less defines how Zionism and Israel are judged by leftists around the world) is traceable to the late-eighties and the rise of Post-Zionism. Seeing the 1990s Peace Process as vanishing mediator makes visible the historical contingency of the interpretation of Zionism that this Leftist project produced, an interpretation whose historical moment has passed. As a consequence, one is freed to construct a new Leftist understanding of Zionism and Israel — and with it a radical reinterpretation of everything that is related to it, just as the Post-Zionists themselves have done.

In the remainder of this essay, I will try to present the contours of a new interpretation of Zionist history. I will periodize the existing understandings of Zionism to have two previous moments. The first I will call the national interpretation, according to which the establishment of Israel is the result of Zionism’s success, the latter considered a collective project aimed at national liberation of Jews. This interpretation was hegemonic since the establishment of Israel until the late-eighties. The second one is the Post-Zionist understanding of Zionism. Here, too, the establishment of Israel is the result of Zionism’s success; yet here Zionism (and the state it has produced) is considered an oppressive collective project.27 In contrast to these, the new interpretation that I will suggest below re-narrates the story as follows: The establishment of Israel was not the outcome of the success of the Zionist collective project, but rather the result of its failure. That both previous readings of Zionism will find their moments of truth in this narrative will become clear in what follows. More importantly, as I try to show, this new reading renders the present once again a space of historical practice, or makes it possible again to view the contemporary condition as an ongoing collective project over which we can collectively exert agency. But one must begin with trying to answer a much more modest question: if the Zionist project is now to be considered a failure, what, exactly, did it fail to achieve?

Borochov, or the Point of View of Totality

The answer to this question will initially seem anything but a new one: Zionism should be thought of as a collective project aimed at providing European Jews with agency over their own lives — agency conceived as a reconstituted collective subjectivity, or self-determination. This does not mean that all Zionists pronounce their goal to be self-determination; rather, their explicit goals can always be seen as forms or thematizations of this deeper goal of self-determination. In this sense, one should distinguish self-determination from its specifically nationalist variant. One should maintain a hermeneutical tension between the explicit, stated goal of this or that variant of Zionism, and self-determination as this stated goal’s interpretation — which necessarily remains hidden (much like Freudian dream content). This would mean that even when Zionists explicitly mention self-determination as a goal, they are not referring to what I mean by this term (be it self-determination as cultural autonomy from the Czar, or struggling for self-sufficiency of this or that settlement). In other words, A certain interpretive distance has to be maintained between their use of the term to designate this or that political goal, and my hermeneutical use of it here. These belong to two different registers of the conceptualization of the problem (echoing in this regard that strange Freudian interpretive “rule” according to which everything is about sex, except when sex appears explicitly in the material to be analyzed). This separation of the register of overt content from the hidden one has the following important implication for the argument that I am making. By positing self-determination as the true (hidden) goal of all Zionism, I am not preferring one branch of Zionism (those that emphasized precisely that as a goal) over the others. No, in the interpretation presented here, all Zionists are equally present before us a thematization of — or a complex figure for — this goal of self-determination, regardless of their usage of the term “self-determination” itself.

My first interpretive scene (and others surely could have been chosen) will take us through an all too brief examination of the writing of one of Zionism’s most interesting theoreticians, Ber Borochov. I will focus on the eclectic thinker’s more Marxist texts from1905-1907, the most comprehensive of which is Our Platform, written for the Workers of Zion party.28 Generally, Borochov is thought to have “synthesized” historical materialist analysis with Zionism by arguing that Zionist colonization is an inevitable result of capitalist development, an argument on which I will have more to say in what follows. One should briefly mention the way Borochov is usually read in the two previous interpretive traditions that I have mentioned (the national one and the post-Zionist one), if only to make clearer their contrast with the new interpretation I am offering here. The national interpretation of Borochov generally highlights his advocacy of the establishment of a Jewish territorial autonomy in Palestine, minimizing or neutralizing his insistence that “our ultimate goal is socialism,” or his debunking of any notion of national interest that exists separately and beyond class interest.29 Here, to give one example, belongs Gutwein’s attempt to argue that Borochov’s “Marxist” period should be chalked up to Borochov’s political maneuvering rather than seen as his genuine position at the time.30 Here, too, belongs Matityahu Mintz’s detailed exploration of Borochov’s position in terms of the political struggles within Zionism, going as far as arguing that Borochov’s 1905 essay “Class Moments of the National Question” posits the primacy of national consciousness over class consciousness — in direct contradiction with Borochov’s actual argument in the essay.31 If the national interpretation downplays Borochov’s Marxist commitments and celebrates his national ones, the Post-Zionist one presents us with the diametrically opposed position. Namely, that Borochov’s great theoretical contributions to social science should be separated from his arguments for Zionist settlement of Palestine, considered by Yoav Peled — whom I take here to be representative of the Post Zionist position — to be worthless propaganda.32 It is clear why Borochov has never garnered much attention from Post-Zionists: for a “purer” analysis of class and national conflicts one could simply turn to other thinkers.

The symmetrical antagonism between Peled’s Post-Zionist position and Gutwein’s national one should be evident here: What is significant about Borochov’s position for Gutwein (the call to colonize Palestine) becomes merely cynically utilitarian or propagandistic for Peled. What the latter considers worth saving in Borochov (namely, the universal Marxism or social theory) is merely political maneuvering for the former. In this essay, I will not be able to examine each of these positions at any detail, beyond merely noticing the unsurprising centrality of Borochov’s view of Jewish national aspirations to the disagreement between them. What my new interpretation will suggest in this regard is that one should try to refrain from reading the category of “nation” in Borochov’s writing from within our set of cultural attitudes — in which the failures of the Israeli nation-state tend to make us suspicious of any support of the nation. Rather, one should notice that from Borochov’s perspective, particularly that of 1905-7, Jewish territorial autonomy was very much a site of imaginary speculation, of utopian construction and remote possibility, rather than a concrete historical entity.

It therefore becomes more pressing to suggest a different interpretation for this central category of Borochov’s thought. I would like here to propose that one read Borochov’s usage of “nation” as what produces a movement of thought the appropriate term for which will only become important within Marxism in the writing of Georg Lukács, namely, the thinking process that tries to achieve “the point of view of totality.”33 What hides behind “nation” is no other than the working of the capitalist system is precisely what Borochov hints at when he argues that

The relationship between a specific oppressor and a specific oppressed person does not play an important role in national conflict: the personal character of national clashes is here bound in immediacy with the impersonal nature of national oppression. While the anonymous, systemic nature of class exploitation is revealed only after a lengthy inquiry, national oppression exhibits its impersonal nature immediately. Thus, the oppressed Jew does not blame the single non-Jew that stands before him for his troubles; No, he is oppressed by a whole social group, and initially he cannot fathom his social relation to this group.34

It is important that we notice the double meaning of “nation” for Borochov. “Nation” is the form of appearance taken by systematicity itself for the individual Jew: national oppression seems immediately impersonal. But, at the same time, the oppressed individual is stuck in this immediacy: she cannot, through the category of the nation itself, understand her social relation to other national groups. It is in this way that “nation” becomes a code or a placeholder for something like the capitalist totality itself: it both signifies immediately the systematic, structurally-causal nature of capitalist oppression while at the same time the category of “nation” itself, as a placeholder, stands in the way of mapping one’s insertion into the real social relations of that totality. Obvious here is that “national” oppression does not constitute merely an additional oppressive dimension of Jewish life, one that has to be simply added to the class exploitation and oppression. Rather, national difference is both necessary and something to be overcome: it is necessary since it preserves as sense of systematicity and it needs to be overcome if Jews are to understand their position within that system. It is a matter of course that “Jew” as a signifier stands to lose its sense as this dialectical process unfolds.

It is in this way that “national” considerations are always a starting point (but never an endpoint) that allows Borochov to present a totalizing analysis of Jews’ social position within European class society. Antisemitism is for Borochov not a form of oppression external to capitalism, but a precapitalist social division adapted under capitalism to fuel the competition between workers who have nothing but their labor-power to sell.35 The isolation of Jewish communities and the flourishing of Yiddish are both taken by Borochov as signs not of some Jewish national essence, but precisely the result of the intensification of capitalist social relations. Jews cannot engage in class struggle with capital, according to Borochov, precisely because of their exclusion from primary production, finding themselves instead concentrated in small production of consumer goods — in which the organization of workers is almost impossible and no economic pressure on capitalism can be exerted. More importantly for Borochov, Jewish immigration is not primarily a result of political commitment or willful Zionist (or other) effort, but a result of the intensification of competition among workers and the petite-bourgeoisie. The totalizing kernel here is that rather than seeing Jewish immigration as an abstract solution, a reified positive goal abstracted from social reality, it should be seen as capitalism’s own attempt to “solve” its contradictions through geographical displacements.36

Borochov’s totalizing analysis has one crucial aspect for my purposes, which is that Jewish workers’ historical agency — their “control of their own fate,” as Borochov puts it — will not be achieved through establishing a Jewish political or cultural autonomy in Europe. Nor could it be a direct result of a Jewish colonization effort of Palestine: Borochov emphasizes countless times that the dependency of the colonization effort on capital prevents any true proletarian agency over history or any reconstitution of self-determination. Rather, directing and organizing Jewish immigration into Palestine amounts to no more (but also no less!) than establishing the preconditions for Jewish workers engaging in struggle against capital:

We would consider the Jewish problem completely solved, we would consider the anomalous nature of the Jewish proletariat completely gone (to the degree that it is at all possible within the bourgeois market), were we to obtain a territorial autonomy for the entire Jewish people, if the latter were to be concentrated in its unique territory and would establish there an independent society, a single, whole, economic organism.37

And while a territorial state might be the Jewish bourgeoisie’s ultimate goal, it would only constitute for proletarian Zionism a “transitional phase on its way to socialism.” And Borochov does not neglect to add that such economic autonomy would only be relative under global capitalism. It should be clear at this point that “national territorial autonomy” for Borochov is primarily a code word for relative economic self-determination — a capitalist contradictory totality. In this way, Jewish immigration into Palestine and the establishment of a “territorial autonomy” — a state — can only in Borochov’s analysis set the stage of history, as it were, for Jewish participation in worldwide communist revolution, or for Jewish proletarianization. Immigration and statehood is not in itself part of a revolt against the bourgeoisie, but in fact acting in its interests. Thus, the “national question” or the “Jewish question” names for Borochov the mediated form in which one discusses the way Jews can take part in proletarian class struggle rather than fulfill some ethnic or other essence.

It is precisely for this reason that Borochov objected to the establishment of collectivist settlements as some ultimate horizon of proletarian class-conscious act in Palestine, which brought him into direct confrontation with the majority of socialist Zionists leaders, as Gutwein reminds us.38 The collectivized nature of early agricultural colonies, Borochov insisted, is a necessity for early capitalist development; the ultimate dependence of modern agriculture on the world market — for credit, machinery, and as a market for their products — is what prevents these settlements from constituting directly a communist society, as Borochov argues, even if they can potentially be a breeding ground for socialist tendencies.39 That he later in 1917 ended up retracting his objections and finally supporting the “constructivist” approach (the one that supported cooperating with the bourgeoisie) already foreshadows a historical dilemma that will emerge fully in the next section of this essay.

In this way Borochov’s writing becomes an important node or coordinate in my attempt to reinterpret Zionism: if capitalist statehood is by no means the final goal of the Zionist effort, if Zionism as Jewish workers’ self-determination, or their reconstituted collective agency, can only be achieved after a prolonged class struggle with the bourgeoisie in the future state, then Zionism has so far failed to achieve its historical goal. Rather than the establishment of the state of Israel signifying the successful completion of Zionism’s goals, it can actually now mean the historical expression of Zionism’s failure. Both the national and the Post-Zionist views of Zionism find their moment of truth here: the argument presented here fully agrees with the Post-Zionists that Zionism’s failure has created an oppressive system, but at the same time it shares with the national interpretation the view that Zionism was aimed at liberation, or at gaining human agency over history. The difference lies in the fact that in this new interpretation, Zionism becomes an unfinished business, a fragment of an incomplete historical process (or, in a more theoretical vein, one of those Benjaminian ruins of history). More importantly, it opens up a way to no longer see Zionism as some kind of out-of-reach museum exhibit, merely panorama to a permanent present. Instead it transforms this present into a space in which the “Zionist” project is still being made by us collectively, consciously or otherwise.

It is crucial to emphasize that reinterpreting Borochov’s writing in this way does not mean that one must take his position or necessarily agree with him. The opposite is true: I am here not following the letter of Borochov’s words (which would have us again wrestling ethically with his “support of nationalism”) but rather recoding his concerns using the hermeneutical apparatus I have tried to develop. It should be clear that Borochov’s response to the social contradictions of Jewish existence in Europe is only one among many, and all of these can be interpreted — usually much more easily than Borochov — to be about achieving Jewish self-determination. I have singled out Borochov’s writing here for two main reasons: first, it is very easy to show, as I have tried to do, how both national and post-Zionist interpretations of Zionism very crudely appropriate Borochov’s thought (as opposed to the writing of Ben Gurion, for which one would have to go through a lengthier historicization in order to revive its original ideological operation of striving for not-necessarily-national self-determination). But the moment one clears away these interpretations, Borochov’s writing seems to defy easy interpretation. In this situation a new interpretation of his work becomes a pressing necessity. Secondly, I choose Borochov because his writing helps demonstrate how a new way of interpreting Zionism, such as the one that I am developing here, is sorely needed.

Zionism in the 1920s, or the Dilemma of Autonomy

The Zionist settlement project itself in the 1920s provides a different entry point into the interpretation of Zionism. If Borochov’s 1905-1907 writing is more concerned with the transformation of Jewish social and political life in Europe, and consequently treats the organization of Jewish immigration to Palestine as a speculative exercise, this is not at all the case in the 1920s Jewish political and social field that has meanwhile developed in Palestine (an effort that gained momentum when the British took control of Palestine after WW1). While for Borochov, as I have tried to show, Jewish workers’ agency over their lives is relegated to the post-colonization future, the Zionist workers in Palestine can no longer hold revolutionary action at a safe distance from their everyday lives. The view according to which a socialist revolution will only occur after immigration is no longer helpful once one has immigrated. The new interpretation suggested here stands or falls with our ability to provide a new set of coordinates for understanding the actions of Zionist movements in this context, one which would also have to include in a non-trivializing way what we called the national and the Post-Zionist interpretations of this period in the history of Zionism.

One of the central points of contention is the role of new social forms that emerged in Palestine. The national interpretation sees, as can be expected, the 1920s as an uninterrupted link in Zionism’s effort to achieve statehood. The 1920s, according to S.N. Eisenstadt — who undoubtedly belongs to the national camp — is the period in which Zionist ideology had finally adapted to the condition in Palestine, producing sustainable collectivized agricultural settlements, supported by a labor organization (the Histadrut), that coordinated employment and settlement efforts.40 The cooperative nature of the kibbutz is hailed as the key to the success of the nation-building effort, and the ideologemes of self-sufficiency and personal sacrifice are amply invoked. Conflicts within the Jewish colonization effort — not only between Jewish and Palestinian workers, but also between different Zionist organizations — are usually omitted or made non-threatening in the national accounts. (see for example Elkana Margalit’s or David Zait’s accounts of conflicts between different Zionist movements, in which the discord is always staged as a friendly disagreement, one that never threatens a deeper union or alliance).41

The Post-Zionist interpretation of the same period is the inverse of the national one. According to Gershon Shafir’s writing, by 1914 Zionism’s socialist aspirations have become just a convenient illusion (or an outright lie), covering up what is essentially an exclusionary colonialist effort of nation-building. The previously-celebrated social form, the kibbutz, is revealed to be in Shafir’s account nothing but a nationalist solution to the problem posed by competition between Jewish and Palestinian workers in Palestine: the kibbutz’s collectivization allowed for lowering the reproduction costs of Jewish labor, making it more competitive with Palestinian laborers and making it possible to keep labor, at least in part of the economy, completely Jewish.42 What was previously, in the national account, seen as a social form that led to Jewish emancipation, becomes for Shafir and other Post-Zionists a tool for preserving Jewish ethnic purity or for creating an economic system autonomous from the Palestinian one, as Lockman puts it in his critique of Shafir’s work.43

Common to both of these accounts is the reductionism of their account of Zionist social form. First, it is important to register that the kibbutz was by no means the only social innovation in the 1920s. Many other forms of organization of social life were suggested and tried by the different movements of colonists-immigrants (in which the degree of collectivization was not the only variable): self-sufficient single agricultural settlements; small or large networks of settlements — either loosely related or strongly centralized — that support each other economically; networks that included a mixture of urban and rural groups; alternative forms of labor organization that included Palestinians, etc.44 To that one must add that the word “kibbutz,” which is used in most of these sources to designate a (mobile) group of people who work together, rather a than a physical settlement, as we tend to use the word today — a difference that adds another degree of freedom to the different attempts to imagine how the different kibbutz-groups should be organized.

These different ways of conceiving of the precise form of social organization go virtually unacknowledged in almost all national or Post-Zionist texts. I suggest that all of these different forms of organization should be seen as different solutions to the Zionist problem of self-determination or historical agency, now posed more concretely than in Borochov’s speculative texts. Margalit, for one, describes the different social forms that were suggested and tried as constituting different ways of seeking autonomy from the capitalist market itself, as it became clear that the most formidable barrier to exerting greater agency over one’s life was the dependence on the world market.45 The incorporation of modern technologies into new agricultural colonization efforts both ensures their dependence on the market (for machinery, credit, etc.) and necessitates local cooperation for the development of infrastructure (road systems, ports, etc.). For this reason, Borochov had concluded, one should be wary of seeing collectivized settlements as a positive proletarian victory in its class struggle, since it is in fact working to promote capitalist accumulation. When many in the Zionist workers’ movements realized in the 1920s that it was once again private capital taking away any possibility of exerting control over their lives, they sought autonomy from the market itself: “to take our market out of the market” as Tabenkin put it — and here it is important to add that Tabenkin’s comments are aimed against private enterprise, rather than against Palestinians.46

For example, one movement’s (The Labor Brigade’s) announcement that the period of workers’ participation in the constructive settlement effort is over, and that the time of revolution has come, should be seen precisely as one attempt to imagine how to reassert the goal of self-determination. Ben Gurion’s repeated assertion that proletarian class interest is identical to the national interest — or that workers should support continued nation-building with private capital (and of course labeling that capital “national” does not change its essential functioning as capital) — is yet another possible solution to the historical contradiction between socialist goal and present conditions. The different debates — for instance, whether or not the General Federation of Labor (the Histadrut) should promote proletarian struggle when it clashes with “national” goals, or whether different networks of agricultural settlements should act autonomously from the main Zionist settlement effort (led by Ben Gurion’s Labor Unity party) driven by capitalist interests — should be seen as again suggesting different solutions to the problem of wresting self-determination from the dictates of capital. A third kind of solution was the stage-ist view that does not make revolution unnecessary, but argues that the time for it has not yet come —which, as I tried to argue, is another imaginary option made available through Borochov’s analysis. One should not underestimate the ferocity of these debates and struggles over the form of organization and course of action that would lead to agency over history — Ben Gurion repeatedly threatened different movements with all kinds of sanctions if they do not toe the line.

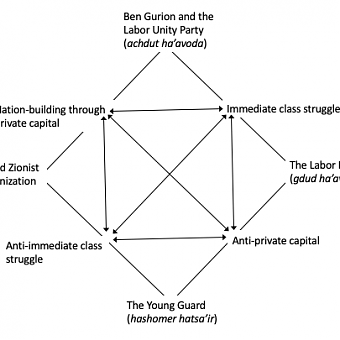

Rather than leaving the field in a state of pure difference or multiplicity of Zionist responses or solutions (as one variety of post-Zionism does), I will try to suggest a typology of these. I would like to suggest that the basic opposition structuring the typology should be one contrasting nation-building using private capital on one hand, and a direct attempt to bring about revolution or proletarian control on the other. A Greimassian square is useful in representing the different modalities opened up through this basic opposition:

The specific movements that comprise the outer square are of lesser importance to us in this context. More important is that one notices that each corner of this outer square represents a possible imaginary and political solution — a Žižekian act that contingently bridges the gap between situation and goal, each producing historicity — that imaginary tying-together of individual action and historical movement. In our upper corner, Ben Gurion’s Labor Unity Party reconciles the opposition in what is a textbook example of Althusser’s conception of the reconciliatory operation of ideology. “Class interest is the national interest,” Ben Gurion and Berl Katzanelson constantly argue: “The realization of Zionism does not take place outside the realities of class, and does not erase the antagonistic interests and tendencies, but it necessitates inter-class cooperation,” as Katzanleson put it, effectively again identifying class interests with national ones.47 This solution ended up being the dominant one among Zionists to the problem of achieving self-determination, leading in the end to the Zionist colonial displacement and expropriation of Palestinians. It is here that the post-Zionist narrative is basically preserved in the new narrative that I am suggesting, rather than rejected.48 Needless to say, this solution led to the establishment of a capitalist state — which from our vantage point can undoubtedly be judged to be a complete failure in terms of bringing about Israelis’ self-determination, not to mention Palestinians’. At the left corner, The Zionist Organization is in the 1920s very anti-proletarian, actively acting to purge the agricultural settlements of socialist ideas.49 On the right corner is the Labor Brigade movement, that had decided to stop taking part in building the infrastructure for capitalist accumulation and instead begin acting towards direct proletarian control, arguing that “the time of construction is over, and that of revolution has come.”50 The Brigade ultimately failed to bring about revolution: working for joint Jewish and Palestinian worker organization and trying to unite urban and rural workers was met with heavy resistance from the Zionist mainstream, and finally condemned the Brigade to dissolution in 1926. These three different types of solutions to the problem posed by Zionism proved, with time, to fail to produce the desired result. But again, it is not their failure which is important to us here, but that all three political and social positions constituted different attempts to solve the common Zionist historical problem of self-determination.

The bottom corner, that of the Young Guard movement, which stands for the negation of both immediate revolution and capitalist development, is the most interesting one — as it captures both the impulse to free oneself of the constraints of capitalist development and also the contradictory impulse to delay active class struggle due to fear of dissolution, or of “liquidationist” tendencies, to use their own terms. I will not be able to trace here the transformations in the movement’s positions throughout the 1920s — in which most creative energies go into the attempt to imagine and bring about the effects of the collectivization of desire and spirituality that must, according to the movements’ theorists, accompany the material collectivization (a problem that in another context can be considered a problem of cultural revolution — how do we transform social practices after we have taken control?). The relentless criticism leveled by the movement’s leaders at Ben Gurion and the actions of the Zionist mainstream makes it clear that it is precisely the attempt to achieve historical agency that is at stake here. In the words of the Guard’s leader, Meir Ya’ari:

The socialist utopia of a worker’s society has been dismantled, piece by piece… the means have become ends in themselves, and the socialist goal has as if disappeared… the huge institutions that have been established have gradually come to serve only their self-preservation… the cooperative movement in the construction branch was destroyed. And Solel Boneh [Zionist construction company]… with a huge perennial bureaucracy, but employing a multitude of temporary construction workers that come and go… this is how the cooperative element in the housing project is eliminated. The autonomic framework of the Federation of Labor’s educational program has eroded away as well.51

The extraordinary self-documentation of the movement’s first utopian settlement, as well as scholarly writing about the movement’s travails, captures the tortuous path it has chosen — one that tends to leave painfully open the historical contradiction in which it is found.52 On one hand, seeking all manner of autonomous existence after repeatedly rejecting Ben Gurion’s unconditional support of capitalist development. On the other hand, refraining from putting their kibbutzes (“kibbutz,” again, taken here to mean a group of people working together for a common purpose) on too direct of a collision course with the hegemonic Zionist institutions, a confrontation that they feared they would lose. The fact that the early years of the Young Guard movement continue to haunt the Israeli imagination — evident in the 1970s play by Yehoshua Sobol about the Guard’s first settlement, all the way up to Yiftach Ashkenazi’s reflections on the Guard in his 2014 novel Fulfillment — is perhaps the best evidence that a utopian impulse associated with the Guard’s refusal still exerts its force on the Israeli collective psyche.53

Yet it is important that one does not become too enamored of one’s object: The Young Guard’s rejection of both poles in the basic opposition (revolution versus capitalist development) ends up constituting simply another failure in terms of the basic problem posed by Zionism. Much like the other movements or solutions, it failed to generate the much longed-for self-determination, or agency over history. This failure is expressed in the Guard’s final degeneration into a domesticated minority opposition to Ben Gurion in the 1940s. No longer threatening politically, it is relegated to stand for some ethical purity instead.

One possible objection to my attempt to chart the different Zionist positions using a Greimassian rectangle is that it is reductive — or that it ignores a much complex multiplicity of Zionist positions. One should however keep in mind that all periodizations are necessarily reductive operations, as Jameson reminds us. It is possible to take both Post-Zionist and Israeli-national interpretations of Zionism as clear examples of this reductionism: the former demanding that we see the entire historical period in terms of a racist colonial project, while the latter requiring that we see it as dominated by liberating nation-building. The point here is not that both of these are wrong because they are reductive, but that reduction is necessary for periodization and therefore for historicity itself. And this sort of reduction is not limited to history, but has to do with the working of our imagination in general: it is the problem of “cognitive mapping,” and also the problem of imagining the subject of history. But it is also the problem of constructing a figure which can somehow stand for a multiplicity that Freudian dream-work tries to overcome with its condensations and displacement. I suggest that one should view this sort of reduction as a creative solution — one that has its limits, to be sure, but that nonetheless makes possible certain imaginary operations that otherwise remain out of reach.

But to this can be added another, more practical, defense of the Greimassian rectangle: In fact, it leaves much more room for complexity than these other periodizing schemas. Since each of the four positions actually represents a combination of two simpler (non-composite) positions, one can add these four simpler positions to the four, which makes it a total of eight (and this is without counting the relations between many of these eight positions implicit in the square). This is not an empty numerical measurement: a good example of why it is not is the Brith Shalom (“Peace Covenant”) movement — a small group of bourgeois intellectuals, a non-entity in terms of real political power, but one which is dear to the heart of the Israeli liberal Left, which can also be mapped using the square. The movement’s ethical rejection of the nation-building project because oppressive towards Palestinians (which it surely was), belongs in the anti-private capital nation-building corner of the inner square (bottom right). That Brith Shalom never took a position for or against immediate class struggle distinguished the movement form both the Young Guard (that rejected immediate class struggle) and from the Labor Brigade (who supported it, and for whom a united front with Palestinians was necessitated by this demand for immediate class conflict). It could even be said that the Brith’s absence of a clear position regarding immediate class struggle made it relatively unpopular in the first place. When we understand the square in this way, movements such as Brith Shalom, which seems at first glance to have very little to do with my concerns, are not here “reduced away,” but can rather still be represented on the Greimassian square, however imperfectly.54 This hopefully suffices as a demonstration that the necessary operation of reduction does not threaten to eliminate all complexity or multiplicity from the field, but simply gives this multiplicity an order or a form — even if different than those to which we are accustomed.

It becomes possible now to return to the starting point of this section — the attempt to outline a new interpretation of Zionism according to which the establishment of Israel is a result of the failure of the Zionist project, rather than its success. It is important again to show that both the national interpretation of Zionism and the Post-Zionist one have their moment of truth in the new narrative suggested here. I have tried to argue that the different attempts in the 1920s to realize the conditions for Jewish workers’ historical agency ended up in failure. What distinguishes the Post-Zionist view is precisely its sensitivity to Zionism’s failure to produce subjects that are free to determine their own lives — be they Palestinians or Israelis. On the other hand, the national interpretation’s insistence on the liberating impulse at work in Zionism also gains a localized validity in this new reading — for this impulse is precisely what animates each of different solutions suggested in the 1920s to the Zionist predicament.

The final point that should be emphasize is that this new interpretation has the potential of making the Israeli present into a space of collective action once again, reviving an imaginary relation between past and future that the Israeli Left has been lacking since the vanishing of peace as a political goal. Seeing Zionism as a failure, as a collective transformative project that has stalled, makes it possible again for us to perceive the Israeli present as a result of Zionism’s unfinished business, as some work-in-progress that we are still in the midst of producing, and whose goals it once again becomes possible to take up and make one’s own, even if it is of course impossible to be again a Zionist in the older sense. The Zionist project I have been describing was never limited to Jews only. The constant clashes about cooperation with Palestinians, the feminist valences of the Zionist project whose traces one can find in all of the realist literature of the period, and the experimentation with sexuality that were part of the Young Guard’s first settlement are all are part of the stalled struggle for self-determination that was Zionism.

It is not the case that a new version of history alone can magically put into motion a renewed historical movement; the latter can only be affected by an actual transformation of social form, an actual social movement or organization whose own actions would somehow have to match a new sense of historicity. From this perspective, the new historical interpretation suggested here is a kind of voluntarist falsehood: an attempt to restart historicity without having a new social form as its base. But this is in a way the only right way to be wrong: yes, it is only a voluntarist illusion that one can simply will oneself out of the postmodern crisis of historicity. But it is the only way of failing-to-have-historicity that might result in movement. In this sense, adopting the historical narrative suggested here could be the beginning of another vanishing mediator: its agents could be wrong, but history can nonetheless take its course through their actions.

The pressing need for such a new narrative could not be clearer. The need for self-determination is surely felt as strongly today — by Israelis radically impoverished by neoliberalization, as well as by Palestinians oppressed by Israel — as it was in the different Leftist Zionist movement. As Gutwein argues, one should think of the Israeli Settlements in the West Bank as a geographical “solution” for the contradictions of capitalism in Israel/Palestine: privatization and the rolling-back of welfare-state social protections forced impoverished Israelis to look for cheaper housing, which could only be found in West Bank settlements (since real-estate in Israel was becoming an important commodity in the accumulation of capital). Thus, “the universal welfare state that was being dismantled in Israel was reestablished in the occupied territories,” as Gutwein succinctly puts it.55 To stop the Israeli settlement operation in the occupied territories, therefore, required fighting neoliberalization, rather than mounting a direct political attack on those displaced by neoliberalism: the inhabitants of the settlements. Just as Zionism, in the new view of it presented here, was an (failed) organized struggle against the contradictions of capitalism that drove Jews to immigrate from Europe, the new struggle is aimed both at freeing Palestinians from Israeli oppression and against the contradictions of neoliberal capitalism that drove Jewish Israelis to the settlements. This is what the new interpretation of Zionism offered here — one that sees it as a failed collective project aimed at self-determination, rather than an ethnic cleansing program — makes thinkable.

- I would like to thank Nicholas Brown for his comments on his essay.

- Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (London: Verso, 2007) and Eyal Weizman, The Least of All Possible Evils: Humanitarian Violence from Arendt to Gaza, (London: Verso, 2011).

- Eric Cazdyn, The Already Dead: The New Time of Politics, Culture, and Illness (Durham: Duke UP, 2012) 6.

- Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, The Global Political Economy of Israel (London: Pluto Press, 2002) 3; Michael Shalev, “Have Globalization and Liberalization ‘normalized’ Israel’s Political Economy?” Israel Affairs 5.2–3 (1998): 126.

- Bichler and Nitzan, The Global Political Economy of Israel 348; Dani Gutwein, “He’arot al hayesodot hama’amadi’yim shel hakibush [some comments on the class foundations of the occupation],” Teoriya ubikoret 24 (2004): 204–5.

- Tamar Gozansky, Hitpatkhut hakapitalism bepalestina [The Formation of Capitalism in Palestine] (Haifa: University of Haifa Press, 1986) 69-72.

- Zeev Sternhell, The Founding Myths of Israel: Nationalism, Socialism and the Making of the Jewish State (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1997).

- Fredric Jameson, The Ideologies of Theory (London: Verso, 2008 [1973]) 309-43; Slavoj Žižek, For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor (London: Verso, 1991) 179–227.

- Žižek, For They Know Not What They Do 183.

- Jameson, The Ideologies of Theory 330–32.

- For a sympathetic account of Zionist efforts to achieve peace, see Yosef Gorny’s, Zionism and the Arabs 1882-1948: A Study of Ideology (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987). For a critical account see, Avi Shlaim, Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement and the Partition of Palestine (New York: Columbia UP, 1988).

- Theodore Herzl, The Old New Land (Berlin: Seemann Nachf 1902).

- Laurence Silberstein, The Postzionism Debates: Knowledge and Power in Israeli Culture (New York: Routledge 1999) 1–4, 89–126.

- Silberstein, The Postzionism Debates, 93-6 and Eran Kaplan, Beyond Post-Zionism (New York: SUNY Press, 2015) 4.

- Benny Morris, “The New Historiography: Israel Confronts Its Past,” Tikkun 3.6 (1988): 105.

- Morris, “The New Historiography” 108.

- Joel Migdal and Baruch Kimmerling, Palestinians: The Making of a People (London: The Free Press, 1994) xxix.

- To highlight how this moment in the narrative fits within the vanishing mediator narrative form, it is easy to identify this moment with what Žižek sees as the intensification of the older superstructure in this second moment, or what Jameson sees as the freeing of rationalization to take root outside the monasteries everywhere in the social structure under Calvinism — this is precisely what takes place when peace-making becomes something to be pursued outside the institutions of the Israeli state — which is to say, everywhere (see Žižek, For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor and Jameson, The Ideologies of Theory).

- Daniel Gutwein, “Left and Right Post-Zionism and the Privatization of Israeli Memory,” Journal of Israeli History 20.2–3 (2001): 17 and Silberstein, The Postzionism Debates 107.

- Michael Feige, “‘Ze Sipur Al Hamakom Veze Hamakom’: Dionysus Basenter Vemabat Nosaf Al Hahistoriographiya Ha’yisraelit,” Teoria Ubikoret 26 (2005): 205; Laurence Silberstein, The Postzionism Debates, 125.

- Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford: One World Productions, 2006).

- Yagil Levy and Yoav Peled, “The Utopian Crisis of the Israeli State,” Critical Essays on Israeli Social Issues and Scholarship: Books On Israel, vol. 3, eds. Russell A. Stone and Walter P. Zenner (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1994) 202.

- Levy and Peled, “The Utopian Crisis of the Israeli State” 209.

- Baruch Kimmerling, “Patterns of Militarism in Israel,” European Journal of Sociology / Archives 34.2 (1993): 211-12.

- For They Know Not What They Do 188.

- For They Know Not What They Do 189.